How To Be a Dope Ass Motherf#&ker: Writing for Hire Tips with Steven Bagatourian

Jake: My guest today is Steven Bagatourian. Steven is an award winning writer. He wrote All Eyez On Me, the Tupac movie. He’s done huge budget features. He’s done tiny little independent films. He’s done everything in between. He’s also a tremendous mentor here at the studio, working with some of our top writers in our Protrack Mentorship Program and our Workshop Program. And so thank you, Steven, I’m so glad to have you on the program today.

Steve: Thank you so much, Jake, for having me. It is a pleasure to be here.

Jake: I’d like to start off by talking to you about work-for-hire projects. Because so much paid work comes out of the work-for-hire world. You’ve worked on projects that originated with you, and you’ve also worked on projects that are not original, that have come from producers. And I’m curious, how do you find that passion and voice when you’re working on a project that didn’t start with you? And how do you bring that when you’re working on an assignment?

Steve: That’s a terrific question. And it’s something I think that a lot of screenwriters don’t really give enough thought to when they get into screenwriting. Because so much of learning to write screenplays is so focused on (especially on the feature side) spec scripts and original scripts, but then you find yourself in the business and all of a sudden you’re in bizarro world. It’s a complete reversal of what you’ve been doing the whole time you’ve been like learning to write!

The dirty little secret of screenwriting is that over 95% of the work you’re going to get as a professional is going to be on assignment. And so it’s a very specific skill set, to speak to your question directly, it’s a very specific thing to learn how to bring your passion and your voice to an idea that you didn’t originate, that might be dealing with a subject matter you have no particular interest in.

And I know, for me, it was one of the biggest struggles in my career, because it was terrifying. And it’s very much on the job training. You’re hired by a studio, they say, “we’re making a movie about a wacky person who is a dentist, and he’s got some problems with his family,” and certainly you’re passionate about dentistry! Like, oh, who’s not? And you’ve got six weeks to deliver a draft, go!

And on some of my early jobs, it was really scary to me, because there’s a legitimate reason to be afraid at that point. If you mess up, then it’s going to be difficult to continue to work in that space.

So, at the beginning, I tried way too hard to follow instructions and meet the brief that I was given by the studio executives, and I naively thought that they wanted you just to listen to them as a screenwriter. And I quickly found out, that is actually not what they really want.

They want you to hear their notes and hear the spirit of their notes, but then they want you to do something creative and original and address the heart of the note, without literally just becoming a dictation machine for their idle musings and the things that they happen to just throw out in a notes meeting.

They understand that you might have a better idea, that you hopefully will have a better idea, but you’ve got to figure out how to make it your own.

And so, my first couple of assignment jobs, I was miserable with the drafts that I turned in. And at the end of the day, when the assignment was done, I was left with nothing, because the studio decides, “hey, we’re going to go another direction.” They’re either not going to make it, or they’re going to make it, but they’re going to bring in another writer. And I didn’t even have a sample script I was proud of to show for the time I spent on the project. That was really upsetting to me, on top of the thought of people reading those drafts, and thinking that that’s what I do!

So I resolved fairly early in my career, after my first couple assignments, that I was never going to fall into that trap again, of writing what they wanted on an assignment. Instead, I had to flip the way I was thinking about it, be more confident as a writer and as a professional storyteller, and just remember that these people hired me because, ostensibly, they like what I do. And I’m the professional storyteller here. And, of course, I’m going to listen to everyone’s opinions, and I’m going to be collaborative. But at the end of the day, it’s my name on the script that says, by Steven Bagatourian. So I have to feel like I’m putting myself in there.

I really started getting a lot more weird and idiosyncratic with my approach to studio assignments, and I found, strangely, that the more I did that, the more the studio executives would actually like what I was turning in, and the more I would get studios wanting to hire me, and companies wanting to hire me for repeat jobs, because they liked the passion and the spark and the sort of kinetic energy that they would get back from my assignments.

My assignments would feel almost like they were spec scripts, because I would approach them in such an odd way and push the characters to the front, as if it was a story I’d wanted to tell my whole life and I had this very unique perspective on it.

But that was a tough skill to develop, finding my way in. And in a way, the thing I love about assignments is that you don’t have time to overthink. I’m sure you can relate to this. As a screenwriter, we’re all very neurotic. We all are constantly having the decision fatigue of being a screenwriter, because any story we write is hundreds upon hundreds upon thousands of different distinct discrete decisions that we have to make. And it’s mentally taxing, but it’s also scary, because at every point, you’re wondering, “oh, could I do it this way? Could I do it that way, could this character instead be a little more like that?”

You don’t have time for all that questioning on an assignment. You’ve got to just pick a lane, be bold, and go for it. And for me, once embraced that, instead of work-for-hire assignments being terrifying, it started to feel like there was something invigorating about that, and I didn’t have to be too precious with it.

You don’t have time for all that questioning on an assignment. You’ve got to just pick a lane, be bold, and go for it. And for me, once embraced that, instead of work-for-hire assignments being terrifying, it started to feel like there was something invigorating about that, and I didn’t have to be too precious with it.

And I think the longer you’re a writer and the more you have confidence that your career is not going to be over tomorrow, the easier it becomes to stop being so precious with every single job and every single draft. You can just take some shots and do what you think is the best thing to do in that particular moment on that particular day. And ultimately, you’ll probably get another bite of the apple. But if you don’t, oh, well! At least, you can look at yourself in the mirror and say, “that’s the best I had that day. That was my best idea on that day.”

And there are times where I look back on scripts I wrote with a lot of pride. And there are times I look back on scripts I wrote and think, “what was I thinking?”

But you can’t overthink everything. And I think as writers, we are constitutionally disposed to overthink things. And it’s a real danger when you’re working on original material that we can go round and round and round in circles for years on a passion project, but then we’ll suddenly deliver something that might be extraordinary on a work-for-hire assignment for a studio, in four weeks!

I never finish my original spec scripts in four weeks! I obsess over them. I obsess over them for months or years and years, and that frustrates me. Because I know that if I’ve got the proverbial gun to my head with a studio, and there’s a paycheck and my career hanging in the balance, I know that I’m capable of writing a lot faster. And writing at a high level quickly.

But it’s still a balancing act, because you come back to your own work, and you don’t have that same real world deadline.

I’ve heard other writers, like Scott Frank, talk about this before. And it was heartening to me to hear that even someone like Scott Frank, who’s one of the great screenwriters of the last several decades, that he himself had the same issue! That he was frustrated that he really delivered for the studios and he killed himself on studio assignments. But when it came to his own personal passion projects, he would just fiddle with them for years. I could totally relate to that.

So we’re all works in progress. As screenwriters, I’m a lot better at some stuff now than I ever have been. But there’s also aspects of my work ethic where, depending on what’s going on in my life, I’ve got a better work ethic some years than others. And that’s really one of the trickiest parts of being a screenwriter, is balancing your real life with the job. And the studio’s don’t give a crap about your real life, so you just have to figure out how to get the material done. And it’s been, during some of the worst times in my life, that I’ve had to deliver on some of the most high profile, high pressure jobs. And, in general, I’ve done it. But it’s a tricky balancing act.

And I think I talked around the question a lot, but basically, that’s the thing, working on assignments, it’s a really specific muscle, and you just kind of have to jump in there. And it is very, very intense, and at times, really, genuinely scary on-the-job training. But I think if you can go through that process as a writer and come out the other side, it does make you a stronger and more confident writer. You realize, “oh, I can tell a story about anything.” Because it’s not about the story, per se, it’s about your voice, and figuring out an interesting way to tell a story.

Ideas, at the end of the day, are cheap. But your unique voice and the way that you jump in there to tell a story, the angle you take on it… I always tell writers that I work with, it’s important to have a great idea, but I don’t care what it’s about. It can be about anything. It’s really just figuring out how you tap into yourself in a way that feels consistent, that you can depend on, so then you can reach into that bag on a studio project, or on your own personal project. So, all these things keep us sharp.

I think it’s really important as a writer to put yourself in these scary situations, to prove to yourself you can do it. And for me, that’s what the studio assignment world became, and has been. It’s a very high stakes game of chicken in a way! Alright, can you do this? You’ve got a big studio expecting you to deliver, and okay, here we go! You have X amount of time. And it’s an adrenaline rush, but it’s not easy.

Jake: I love what you’re saying about being bold, idiosyncratic, finding your voice. And these are the things that unfortunately, the screenwriting books don’t talk about. And it’s really because, as you know, most screenwriting books are just not written by screenwriters, just like most screenwriting classes are not taught by screenwriters, which is crazy!

But you end up with these reverse-engineered, formula, plot approaches, developed by these brilliant critics who have never written a screenplay. It’s a very fictional way of looking at writing. And so many new writers that I work with come to me obsessed with the idea. Like they are only going to have one idea in their whole life!

And then there’s the terror, “I can’t even talk to anybody about the idea because what if I talk to somebody about the idea and they steal the idea, right? I’m completely screwed.”

And mostly this is a completely unnecessary fear. Of course, there are some people who are dumb enough to steal an idea, but very few people that dumb actually have the power to get a movie made. And the truth is, if you’re pitching the right person, they’ve probably already heard your idea! From another writer. But they’ve never heard it with your unique take, with your unique voice.

My fiance, Lacy, used to work for the CEO of CBS. And he always used to get really angry when a writer or producer would come in like, “I’m going to tell you a story you’ve never heard before.” And he’d come out of that meeting saying “Are you kidding me? I’ve heard every story!” Really. We see the same thing as teachers, we see the same ideas come again, and again, just like when you’re working for hire. You see these same kinds of ideas circle around, and you start to realize that it’s not the idea that matters! It’s not the idea that you’re selling. Ideas are a dime a dozen.

And the truth is, you could take a great idea and make a terrible script. And you can take a terrible idea and make a great one.

And this is one of the most valuable things to learn, because a lot of work-for-hire projects, the producer tells you their “great” idea, and you’re like, “Okay… and what’s the story?”

You’ll get these terrible ideas. And it’s your job to transcend them. Okay, how do I take this terrible idea that somebody wants me to write and turn it into something incredible? Somebody’s optioned the Hungry Hungry Hippos board game, how do I turn it into a movie that actually matters to me? That I can connect to? And I think what you’re saying about boldness is such a good way to think of it. If I knew anything I came up with was going to be accepted, what would be fun? What would be cool? What would be exciting?

Steve: That reminds me of something that I’ve said often, and I should give proper credit, because a friend of mine actually said this to me early in my career. My friend, Marshall Todd said this, and Marshall is an amazing writer. He’s the co-creator of a show on Hulu called Woke, and I’ve known Marshall forever, for like 20 years.

And early in my career, he was giving me advice on pitching. And I remember Marshall said to me, “Steve, when you walk into that room and pitch, have a strong f#cking point of view. You’re not going to get every job by having a strong point of view. But I promise you, you’ll get some jobs. But if you walk in there, and you’ve got kind of a middle-of-the-road, wishy-washy, common take on the material, that you could imagine dozens of other writers walking in there with, then you’re not going to get jobs, because you’re walking in there with a take, that’s going to be just like the other cat who walked in half an hour before you and pitched on that same project.”

So that always stuck in my head. And it was a great piece of advice. And it made me feel really fearless, walking into rooms to pitch, because I always thought, “okay, what’s the worst that could happen? I don’t get this job. But the best that could happen is I get the job, and I’ve got this wild take that I’m actually really excited about. I get to actually take a crack at something that I think is going to be cool! And it’s going to be fun. It’s a left field sort of idea.”

So that always stuck in my head. And it was a great piece of advice. And it made me feel really fearless, walking into rooms to pitch, because I always thought, “okay, what’s the worst that could happen? I don’t get this job. But the best that could happen is I get the job, and I’ve got this wild take that I’m actually really excited about. I get to actually take a crack at something that I think is going to be cool! And it’s going to be fun. It’s a left field sort of idea.”

And some of the biggest projects I’ve gotten in my life, in terms of studio films, have been when I’ve walked in, and I’ve said things that really could have landed like lead balloons. And frankly, sometimes they have. Sometimes I’ve walked in (and it’s a gambit that could go either way) but I’ve walked in, and said to top executives at studios that their take on a project sounds like a disaster. That I think that’s the absolute worst way you can approach a film like this, and if that’s what you guys want to do, then I’m not interested. But let me tell you what I would do with this material…

And that’s a dicey thing to say to a big executive at a studio, because, broadly speaking, that can go one of two ways. They can say, “thank you very much, you a-hole. Looks like you’re not the guy for this job.” Or, in the case I’m thinking of, when I said that to the top exec in the room, the junior execs all burst into laughter! And the top exec was a little prickly, but he said to me, “okay, genius, okay, smart guy. What’s your take on this? Why am I so wrong? What is your take on it?”

And then I launched into a very impassioned pitch on this big, high profile project. And at the end of it, all the junior execs and everyone kind of looked at their boss. And they were like, “Well, that actually is a lot better than what you pitched.” And it turned into a really funny moment where even the top executive kind of grumbled, “actually, we weren’t thinking about it like that, but you’re right. That’s pretty phenomenal. That’s a great take on this.”

And that was great. But it was a gamble. When I walked in that room, I knew it was a gamble. But I also knew I was a dark horse candidate on that job. So in my head, I’m always thinking (hopefully always thinking!) I’m trying to think strategically at every stage of my career, whether it’s how I format my screenplays, what ideas I’m selecting, or just my approach when I walk into a pitch meeting. If I know that I’m not the top candidate for this job, and I’m one of many, I’m absolutely thinking, “how am I going to stand out? How am I going to be memorable? Whether they love me or hate me, how am I going to get some kind of a reaction in the room that’s going to be memorable, that they’re going to be talking about when they go to their lunch break?” Because I don’t want to be boring. I don’t want to be the boring writer who walks in and pitches what the other five writers pitched.

Jake: And because, also, even if you don’t get that gig, then they know who you are.

Steve: They remember you! They remember, “Oh, you were that crazy dude who walked in here and insulted my boss. Yeah, I actually liked your take. But of course, I couldn’t hire you. He hated you.” You know, you stick in their head.

Jake: Yeah there’s a writer named Jane Martin, who doesn’t even know who I am, even though I got her so much work. I was a young producer, and her agent was brilliant. She had this script that, at the time, was unproducible. It was a story of a family dealing with the loss of a child. And at that time, in the late 90s, nobody wanted to make a movie about a dead child.

And this script was so beautiful, you read it, and you just cried for days. Her agent had the best strategy. He would target young executives who didn’t know better. So, he targeted me, and he sent me this script. And I fell in love with the script. And I fell in love with Jane Martin. And I did what every other young executive did. I went to my boss, and I was like, “we have to make this movie! We have to do it.”

And my boss said, “Dead baby…next.” Just like every other boss did.

And what happened was exactly what her agent knew would happen. I got angry. Jane doesn’t even know me. She doesn’t know who I am. But I put Jane Martin up for every open assignment we had. Because I wanted to work with her. And I never actually got to work with her myself. She did write movies for us, but I never even got to work with her! But I put her up for everything that I could put her up for, because I was so moved by that script.

And to my knowledge, that script still hasn’t gotten made. But I still remember it. And it wasn’t just me, this was her agent´s whole game– just shopping this unproducible script that everybody loved and everybody wished they could make.

The other thing is, if you sell a take on the script you don’t want to write, now you actually have to write that script you don’t want to write. And that’s not going to showcase your talent. You’re just going to end up with a dead connection to whoever is producing it, and you’re going to end up fired, all because you sold something you weren’t passionate about in the first place.

Whereas, if you come in, and you’re like, “this is what I want to do. And I know it’s a little crazy, but this is what I want to do.” Best case scenario, you actually get to do what you want to do!

And worst case scenario, you build one of two things, you either build a connection, who’s like, “I can’t believe my boss is going with that crappy idea instead of this great one.” Or you get the person who’s like, “hey, this is the wrong project for you.” But two years later, they call you up and they’re like, “Steven, remember, you had that crazy pitch? Yeah, I think I came up with a way to do it.”

Coming at it with that authenticity is so important. And remembering, you used the word idiosyncratic, but don’t try to be idiosyncratic. Try to be yourself. That’s what will make you idiosyncratic.

If you are working on a spec script, don’t take away the edges of your script. Don’t destroy the friction points of your script because you think you’re going to sell out and make it to Hollywood. Because you’re not going to get anywhere that way.

I’ve always felt there’s a healthy dialectic, a healthy kind of pressure, between the needs of a great studio executive and the needs of a great writer. You want the studio executive’s job, the producer’s job, your agent’s job, your manager’s job, to be pushing the piece to be as commercial as it can possibly be. And your job as the writer is to present the purest possible version of what it should be.

And when those two opposing forces come together in the right way, you end up with a dialectic that makes a better movie, that makes a movie that more people will see, that still does a version of that pure thing you’re trying to create. And it’s a beautiful thing when that happens.

But a lot of writers don’t feel comfortable with that dialectic. They try to remove all the pressure and just give the producers exactly what they want, or what they think they want. And the truth is, if they knew exactly what they wanted, they wouldn’t be spending all this money on you!

Steve: Exactly, that’s how you actually convince them you have value, by bringing something to the table. Like you said… I love that thought that you’re saying to look at it like a dialectic. I never thought about it like that specifically. But that makes a lot of sense to me.

What you and I are talking about is not like, “Oh, I’m going to be an artist, and I’m going to do just exactly my vision, and screw all you.” It is figuring out a way to address the concerns, the needs, etc. of the studio, while still producing something that ideally is a credible piece of art. That is not just a craven commercial stab. Something that has a soul to it. And that might be kind of high minded or new agey sounding, but really, that’s what it is like.

You want to have a spirit to the material, a humanity to the material that is there. And that’s your job. As a screenwriter, that’s literally your job, in my estimation, to make sure that there’s a humanity and ideally, a sense of transcendence in the material.

Even if it’s a dopey Hollywood movie about whatever, you can still have a glimmer of something in there, that you as an artist are in charge of making sure is there. And it’s your job to protect the soul of the piece.

The way that one of my favorite screenwriters, Tony Gilroy, talks about this is finding the heartbeat of a story, and how that is the thing he’s always looking for above and beyond any other concern. What is the heartbeat of the story? And it’s kind of an ineffable thing. But as a writer, when you find it, when you put your finger on the soul of this piece, this is what makes it live and breathe. I’m going to protect this element, or this sequence or this character, within an inch of my life, because this is what the story is.

Jake: So let’s talk more about pitching. People get stuck pitching plot rather than pitching structure, or rather than pitching character. And I wonder… you were saying earlier that you don’t pitch plot when you go to pitch.

Steve: No, I don’t, I’m actively hostile at times toward pitching plot. And I’ll even say things to executives in the room, “look, you guys, let’s be honest, we all know that the plot of the story is going to go through endless changes and iterations, in a best case scenario, as we develop this, and as it moves toward production, in every round, everyone’s gonna have notes. Those are all gonna affect the plot. I don’t really care about that. You guys have read my sample scripts. I’ve been writing stories for a while, screenplays, and I am aware of how to structure a screenplay. But let’s put that to the side for the moment. Because, honestly, the plot could be any one of 1000 different things, and I can give you plot points. But that’s not what we’re here for today. What we’re here for today is to talk about this character, and why they are a broken, messed up person, why they are the exact last person in the world who should have to go through this particular version of hell that this story is going to put them through. But here’s why they’re messed up. Here’s why they’re the perfect protagonist for our story. Here’s the crazy cast of characters they will meet. And here is the arc for all of these characters, how it intersects with the themes and the ideas of this story. Here is the personal crucible of hell they go through and here’s how they come out the other side.”

And if I do my job properly, I’m pitching you an incredibly emotionally engaging story that people, executives, human beings can feel resonance with in their own lives. And so, because you’re pitching character, you’re talking to human beings about things they can feel. And if they can feel what you’re saying, then that’s what you need. That’s where you’ve got people actually excited about a story.

Plot elements to me are just really academic. And there’s an incredibly absurd focus, an overemphasis, I should say, on plot that gets kind of doled out there. And all these screenwriting books by all these so called screenwriting gurus and people who talk about things as if there is a formula.

The formula basically is Western storytelling structure, as identified by Joseph Campbell, The Hero’s Journey, the beginning, a middle and an end. And yes, someone’s going through something that has this metaphorical resonance of a person going through a journey of their life, essentially a heroic journey. That’s fine. But beyond a really broad identification, that this is what we do with Western storytelling, as opposed to European cinema, Asian cinema with other cultures that have different storytelling traditions, other than a broad kind of sense of that, this idea of breaking it down into this taxonomy of, “this is the exact moment this must happen, and that must happen, and this must happen.” I just think that there’s a level of absurdity to that.

The formula basically is Western storytelling structure, as identified by Joseph Campbell, The Hero’s Journey, the beginning, a middle and an end. And yes, someone’s going through something that has this metaphorical resonance of a person going through a journey of their life, essentially a heroic journey. That’s fine. But beyond a really broad identification, that this is what we do with Western storytelling, as opposed to European cinema, Asian cinema with other cultures that have different storytelling traditions, other than a broad kind of sense of that, this idea of breaking it down into this taxonomy of, “this is the exact moment this must happen, and that must happen, and this must happen.” I just think that there’s a level of absurdity to that.

Because the most successful writers who I know don’t think like that! And the people who’ve written these books, that have proclaimed this from on high, (no offense to Syd field or to Robert McKee, or to anyone else), but it’s plain to see that these are not people who’ve had big screenwriting careers.

So it’s odd to me, that the industry, the way that screenwriting has been taught for so many decades, has revolved around a coterie of formulas created by people who’ve never written successful films, and have instead reverse engineered these structures based on films that they’re cherry picking and that they’re using their examples.

But that’s why I really enjoy working with you, Jake. And working with the school so much. It is because, from talking to you about screenwriting, I know that we both come from a very similar place, which is much more character focused. And we’re trying to actually identify the heart and soul of a story, not just fill in these rubrics of “this happens here, that happens there.” Those are the scripts that even if they get bought, because the studio has some interest in them, if it’s just something that follows a formula, the first thing they do is fire the writer!

And then they call up someone else who thinks about writing the way that we’re talking about it. And then those writers are brought in to fix the story. So, when I work with screenwriters, what I always say to them is, don’t think about your structure so much, don’t be the person who, best case scenario, is going to get fired immediately, because you have this over reliance on structure and you’re not writing characters.

To me, the first principle, if we go back to first principles, you have to have a character, a main character, who is engaging and in fact, fascinating. And I always say to writers, I don’t care if your main character is likable or not. I think that’s a false goal. I think your main character has to be only one thing, in my mind, and that’s fascinating.

And some of the greatest characters in cinema history are thoroughly unlikable, but they’re fascinating. Charles Foster Kane, unlikable, he’s a prick. But Orson Welles in Citizen Kane is fascinating. So that’s what you’re going for. And that’s what I always say with writers. A lot of times people are so concerned, “oh, I’m worried about my second act. I’m worried about this, I’m worried about that.” And sometimes I just look at a writer and, kindly and with as much encouragement as I can, but still trying to be honest, I say, “look, I think you’ve got a larger problem here. And the larger problem is that your main character is utterly cliché or utterly boring, and completely not engaging. So before we get to your second act problems, all of that’s academic, all that’s moot if you don’t get an audience and a reader to fall in love or fall into fascination with your character in the first five pages, at the most ten pages, but honestly, I’m thinking five pages.”

People don’t realize how critical it is to do things quickly, efficiently, and dramatically. You’re right, it’s page one, page two, page three. If you haven’t hooked a reader by then, and they’re five pages in and they don’t find your main character Interesting, you’re dead in the water. Forget the rest of your script. I don’t want to talk about the rest of your script.

Jake: You know, it’s like swiping on Tinder. You show up at the coffee shop, and in a minute, you know if you just want to finish your coffee and get the hell out of there, or you’re actually interested in having a conversation. And I think it’s exactly the same thing in writing.

Movies get made because of A-list stars. And you’ve worked with a lot of them. You’re working with Denzel Washington, for example. How many scripts does Denzel have to read? If he’s not hooked on page one, why is he going to do the movie? Why is he going to read page two? He’s got a stack of other scripts of people who would love to work with him.

At the same time, sometimes writers try way too hard to be fascinating, to write fascinating characters or good characters or likeable characters, or unlikeable anti heroes. But trying to be fascinating doesn’t make you fascinating.

So where does fascinating come from?

Fascinating, always, for me, has come from going inside, and asking “what part of this character is me?” What part of this character lives in me? And either, what is it that I don’t understand about them? Or, what’s the odd thing that I see them doing where I don’t even know why they’re doing it? Or, what’s the thing that pushes against what seems to be their dominant trait?

Because I think if you try to write fascinating characters, it’s like trying to write great dialogue, it just becomes pretentious and false. Whereas if you just say, “hey, what actually intrigues me about them?” If you just get curious to see if you can fascinate yourself.

Then it just becomes a craft thing. Because sometimes you are fascinated by the character, but it’s not on the page yet, and then there’s a craft thing about how do you get that fascination onto the page?

Steve: That’s a great point. And I think, for me, a lot of times it has to do with, letting yourself be naked on the page, and not being afraid of being earnest.

A lot of my writing, early in my career, was seen as being very dark, or “edgy”, which is a word I hate in Hollywood. The first script I wrote, that kind of launched my career, was a script about a 12 year old killer. And people thought that was a very dark story. “Oh, wow, this is so provocative.”

It’s this really violent story, where within the first five pages, we see a 12 year old child shoot and kill his own father, shoot him in the chest, seven times. And then, as he tries to escape, a bunch of his father’s friends grab this 12 year old, beat him and leave him for dead in the snow.

That was the opening few pages of the script that I wrote called Weasel that really launched my career. But I never looked at it as a dark, twisted story. For me, it was a very earnest story about a young kid who had been a victim of abuse, and so was his sibling. And in this story, this 12 year old kid was actually standing up for his younger sibling who didn’t have a voice.

I set it in a mythical, futuristic inner city that was something out of The Crow meets Sin City, and I kind of spun it as this urban noir gangster story that ultimately turned into a big mystery we follow, with a detective who catches the case, and has to put the pieces together of why this 12 year old ended up killing his father.

And we see a lot of the details of the story unveil themselves through flashbacks, and it turns out the detective has a crazy connection in his own life to this kid who’s now dead. So it was this sort of twisty escalating mystery, but people saw it as very dark. And they thought like, “Wow, Weasel is such a dark story.”

But the people who actually read it and got to the end of it, were just like, “Oh, you know, this story made me cry, because it was ultimately really sweet. It was a really sweet story, even though all the trappings and the bells and whistles were guns and violence and murder, and blah, blah, blah…”

I hate cynical, ironic storytelling. I hate writers who kind of hide behind a cloak of irony and hipness and pretension. That’s not my bag. And for me, I am trying desperately to tell incredibly earnest stories. And I don’t want them to be boring. I don’t want them to be didactic. And so of course, they get dressed up in metaphor, and they get dressed up in things that could be perceived as dark and crazy and wild and whatever. But ultimately, at the core of it, for me, fascinating, to bring this back to what we were talking about, fascinating characters.

Ultimately, to write those characters, you have to risk being earnest. You have to risk allowing a piece of yourself to really come out in the material, in a way that you might think is going to be too sappy, that’s going to be too this or too that.

But to me, the art of being a storyteller is to walk that line where it’s not sappy. It’s not silly to have a character break down and cry at the end of a story. It’s only silly if you haven’t properly set it up and earned that moment.

I think people are afraid, a lot of times, of emotion. And if you’re afraid of emotion as a writer, you’re in the wrong business. You have to be comfortable enough with emotion. Even if you’re an emotionally maladjusted person in your waking life, (which all of us are to some degree or another), I feel like you have to be the best version of yourself.

When it comes to writing stories, you have to be the version of yourself that you would aspire to be. The version of yourself that’s maybe more broad minded, more empathetic, more willing to sacrifice for other people.

That’s my personal philosophy on writing. I want my stories to have the best of me in them.

So even if I fail in my day to day life at times, as we all do, at being a good enough friend or partner or whatever to people… None of us are perfect, but I feel like we should aspire to be the best version of ourselves in our writing. And to me, that comes back to empathy. And it comes back to just letting yourself have an open heart on the page.

I think, as a writer, if you don’t think about that, you’re ignoring it at your peril. Because it’s an emotional thing that we’re doing here. It’s emotion that’s the key to all of this. And it doesn’t matter how perfectly structured your stories are, if you don’t have real emotion at the core of them, then you’ve got nothing.

When I talk about protecting the essence of a story, that’s what it’s about, protecting that heart and soul that makes people care about a story.

And to do that, you got to go to those places yourself. And it might sound cornball to say to people “oh, I cried while I wrote this scene,” but you should cry!

If you’re writing a scene that’s supposed to engender that emotion in other people, you should absolutely get to that point yourself. And if you don’t, then there’s probably something wrong, you’re probably not pushing it far enough, you’re probably not going someplace that’s really touching you. And so consequently, it’s not going to touch anyone else, either.

Jake: I feel in the same way. I want to be surprised as I’m writing. And I’m always looking for something that I didn’t expect, because I always think if what I end up writing is the same thing I planned, then the chances are that anybody who’s really experienced is going to see all the places that I’m planning to go on page one.

Everybody has walls, everybody’s good at wearing masks, and I, just like everybody else, have the mask that I’m super comfortable wearing. And if you start to peel away those masks, what you start to find is the things that you don’t expect, and the things that you didn’t know you could do as a writer and the things that break the rules.

And that’s where the real growth comes from.

Like you said, selling a script, or buying a script, is an emotional choice. I remember, I started as a producer, and my boss always like, “this is what we’re looking for, these are the quadrants,” and then he’d end up optioning the movie about the mother who abandoned her children, but somehow it was really a gift that turned them into the people they needed to be. And he’d option that movie in different forms, again, and again, and again and again. Why? Because that’s what happened to him! Or better said, that’s how he was rationalizing what happened to him.

At the end of the day, buying a movie is an emotional decision, because it costs so much money. If you have $50 million bucks, don’t put it all into a movie. You’re probably not gonna make your money back. Most movies don’t make their money back. So, there’s no rational way to invest $50 million, or $100 million, or even a million dollars, or even like a $50,000 indie film… there’s no rational way to make that decision.

That doesn’t mean that people are going to do things that don’t appeal to them. Or things they don’t think give them a chance at a return on their investment. But at the end of the day, the one they actually move forward with is the one that creates that passion in them, that creates that emotional effect.

And I’ve always believed, who’s gonna produce your movie? The person who’s your tribe. Your kind of people.

The way that I met Steven was through Ramfis Myrthil, who’s an independent producer who teaches at the studio sometimes. I reached out to him because I was looking for new teachers. And he said, “well, let me introduce you to the guy who’s written the best script I’ve ever read.” And that movie is about to get made, right?

Steve: Fingers crossed. We got a director on board who I love, and I got a great team. So we will see in 2021!

Jake: The way Ramfis talked about Steven, that’s the kind of passion you need to incite in a producer, especially at the beginning of your career. When you’re Aaron Sorkin, the passion you have to incite is, “Hey, I’m Aaron Sorkin, and I’d like to write a movie.” But at the beginning of your career, you need someone to read your script and convince themselves, “I’m going to take a risk on this person.”

Steve: Yes, exactly. And I’ve been so heartened to get that kind of passionate response, and have people who have been boosters of mine, or just people who’ve really gone to the mat and fallen in love with certain scripts of mine. Ramfis has been wonderful, and working with him as an indie film producer has been just a delight, because he brings all that passion to the material.

And it’s like you say about finding your tribe. He’s totally someone who I feel is in my tribe, and I would make movies with Ramfis for the rest of my life. Because he’s brilliant, and he’s hard working, he’s respectful, and clearly he’s got excellent taste!

I really do think that you need to throw that passion in your work, because then it goes out into the world, and it resonates with people, who are gonna then suddenly be vibing with the work in that same passionate way. If you don’t put the passion and the emotion in the work, then there’s nothing for people to hold on to, because, like you say, it is so expensive to make a movie! It’s a massive ask of somebody. And yes, people are risking their jobs, they may be risking the future of their company. It’s a big, big ask. And so, emotion has to be there for everyone, because even the executives don’t want to feel like they’re producing something that means nothing.

Jake: Yeah, that’s it. Having been on both sides as both a producer and a writer, a lot of times we think that producers are these weird aliens who only care about money. And it’s the exact opposite. Everybody likes money. But everybody also wants meaning in their lives. It’s just that a lot of producers very rarely get the chance to actually even talk about that, because it’s so much about who’s attached and where do you get the money from?

And I remember, early in my career, I got to work on a story with a very big producer, who actually went on after that to run a network. And I remember him saying to me, “these meetings are the highlight of my day, because this is the only time I get to talk about this.”

And I wasn’t the only writer that he was working with. But I was coming at him maybe a little bit differently than a lot of the writers he was working with, where it wasn’t just about the plot. It was about, “what are we saying? What is this about? Why does this matter?” And then, once we knew all that stuff, we found our way to figure out how we could make it commercial, and how we could sell it, and all those other layers.

But starting at that place of human connection, first off, is just easier. It’s really hard to come into a room and read a logline “when a man finds out…” It’s so awkward and weird.

But when you’re like, “this messed up thing happened to me when I was 12. And I’ve been trying to make sense of it. And that’s why I’m so attracted to this crazy story about this boy. And no, I didn’t shoot somebody, but I know what it’s like to want to defend somebody and feel like you can’t.” When you open yourself up vulnerably, you make that emotional connection with somebody. And this person is going to have to spend years in a room with you and they know it.

Steve: Yeah, exactly. And I think that’s actually a really brilliant thing to do, Jake, what you just said about opening yourself up and being vulnerable in a pitch meeting, because it also displays a certain amount of bravery and a certain amount of comfort with yourself.

Ultimately, whether consciously or unconsciously, I think that is what executives are hoping to find. They’re hoping to find a writer who can be bold, who can be brave, who can also reveal something of themselves and be comfortable talking about emotions and all these things that maybe you’re not normally supposed to talk about with someone you just met.

But in that context, you’re trying to talk about this highly emotional thing, which is the story that you’re hopefully going to be building together. So yeah, I agree with you, I think it’s a really good thing, not just as a strategic gambit, but also just as a human connection thing, to walk in and say, “Hey, this is the reason why I want to tell this story. And yeah, it’s because this messed up thing happened to me when I was a kid,” or “I had my heart broken when this really horrible thing happened just recently, and this is what I see in the story that connects to me.”

And then whether they say it or not, they are human beings, and there is a part of them that’s going to appreciate you revealing this part of yourself. And it’s going to cause them to engage with you emotionally in a different way. And I think that’s really, really important, because you don’t want to stand on ceremony and just be a robot when you walk into these rooms.

Like you say, a lot of these people, their jobs are stressful and boring. And believe it or not, this might be a highlight, a human interaction with a storyteller.

And I always try to, again, take it back to first principles. When I walk into a pitch meeting, I feel like, okay, I consider myself someone who’s a writer, in this era, right now, it’s movies, or it’s comic books, or it’s TV or whatever, but at a different point in history, not that long ago, in the grand scheme of things, we would have been sitting around a campfire. And I would be telling you a story.

And that’s why I actually love pitch meetings.

My manager likes to tell me that I’m a mutant, because I’m the only writer he represents who genuinely loves pitching.

I love pitch meetings, because I put myself in that mindset, whether it’s an assignment or an original pitch, you’re walking in there, and that meeting room, that antiseptic, quasi hip, Hollywood room, (or today, the Zoom Room), that is your campfire.

And these people are giving you some time, some of their precious time, to spin them a yarn.

And so, if you can walk in there, like you said, and reveal something to yourself, make some kind of emotional connection, and then say, “listen, and this is why this story is the story that I want to tell more than anything else in the world right now. And let me let me tell you about it…” ideally, the rest of their lives can fade away for a little while. And you can get them locked into a little bit of a trance with you. And you can take them somewhere, tell them a story, give their brain and their mind a little bit of a reprieve from whatever they’re stressed about.

And when they come out the other side, it’s like they did see a little movie, they watched a show, they heard a story. And hopefully they come out feeling a little bit invigorated, you know? Like, “Wow! That was a cool story. Thanks!”

Whether they hire you or not, I just always want to take it back to first principles. I’m here. I’m a storyteller. This is my job. And it’s not about being overly strategic. It’s about looking these human beings in their faces, and trying to connect with them. And just tell them a really great story.

Jake: Yeah, I love that about you. And you know, I’m one of those weird mutants, too. But what’s funny is I started the opposite. I started as a person with tremendous social anxiety. I was afraid to even pick up the phone. I was afraid to even call somebody! A pitch meeting with somebody, that was terrible.

Steve: That’s crazy knowing you now, Jake. That is actually crazy, because you seem incredibly comfortable now talking and being out there.

Jake: I ended up with this job as a producer, and I didn’t have a choice! I just had to overcome the fear. And the thing that finally helped me do it was, for one thing, the fact that I just simply had to make the phone call. But, at the beginning, it was painful. I would stand up, I would walk around. Pick up the phone. Sit down. Put down the phone. I’d make up a script, I’d throw away the script. I’d pick up the phone. I’d walk around. I’d read the Daily Variety. All this… just to make a call, right? This is how scary it was.

And what eventually I realized was that I was trying to sell people. And that was just inherently not connected to who I was as a person. But what I was really good at… I was really good at helping people. I loved helping people. I’ve always loved helping people, and I’ve always felt like I’m at my best when I’m helping people.

And so, when I stopped trying to sell and I just started thinking, “I’m gonna figure out how to help them.” If they are willing to talk to me, they must need something, right? There’s something they need, something missing. There’s something that they can’t figure out. And I’m going to help them. I’m not going to sell them anything, but I’m really going to try to help them, I’m really going to try to figure out what they need.

It resonated with me when you were talking about giving them an experience that takes them away from the boredom of their lives. You’re being more authentic, and in that authenticity, you also find your own journey.

I always say to writers, if you want to learn to live a good life, all you have to do is learn to write a good screenplay, and if you want to write a good screenplay, all you have to do is learn to live a good life. Because, at the center of a good screenplay, is just a character who wants something so bad, that they’re willing to make new choices that change them. And they’re willing to put up with the consequences of those choices. And they’re willing to be bold, like you said, and make mistakes, and be idiosyncratically themselves. That’s what’s at the center of a screenplay.

I always say to writers, if you want to learn to live a good life, all you have to do is learn to write a good screenplay, and if you want to write a good screenplay, all you have to do is learn to live a good life. Because, at the center of a good screenplay, is just a character who wants something so bad, that they’re willing to make new choices that change them. And they’re willing to put up with the consequences of those choices. And they’re willing to be bold, like you said, and make mistakes, and be idiosyncratically themselves. That’s what’s at the center of a screenplay.

And when you do that work of writing a screenplay, you actually learn how to be more yourself.

And similarly, if you want to learn how to write a good screenplay, well, then you just have to learn how to live a better life. You have to figure out what you really want, and who you want to be. And then you have to start making choices around that. What’s my theme? Why am I here? What matters to me? And how am I pursuing what matters?

Steve: Yes.

Jake: And then what choices am I making? What is the choice I’m avoiding? How am I going to make a choice, every day, that brings me closer to being the person I want to be, even if I don’t know how to be that person yet, or even if I don’t know how to get there?

And, this is why writing is so cathartic. Why it’s so therapeutic, when you do it authentically, as opposed to trying to manipulate somebody, or sell somebody on your great idea, or get rich quick, when you actually just do the work, it’s therapeutic, because you’re actually taking yourself on a journey. And it becomes therapeutic to the people who read it too. Because it welcomes them into a different way of thinking about their own lives.

Steve: That’s very true. That resonates with me. What you said about the close parallel between writing a screenplay and living a good life. It’s sort of like writing your own narrative of who you are, your “Hero’s Journey” as a person. That reminded me of some of my favorite advice that I ever heard about being an artist. I heard this decades ago.

If anybody knows me, they know that growing up, I was a massive comic book geek and a massive music geek, specifically, hip hop. And the producer/rapper, who is the maestro and the architect behind the Wu Tang Clan, the RZA, I remember sitting in a supermarket when I was in my teens, and I was reading an interview with the RZA, and somebody was asking him, “How does someone become a great producer like you? How does someone become as original as you are as a producer?”

And I remember RZA saying that people asked him that question all the time, and that producers would constantly come up to him and ask “how can I produce beats that are so original and strange and odd and unique? How do you do that? How can I do what you do?” And he just said that he always had to laugh, because people are asking the wrong question.

He would say to them, you could never do what I do. Because you’re a boring person. So any work you make is going to be boring. It’s going to be work that’s made by a dull, uninteresting person who has really common conventional sort of interests.

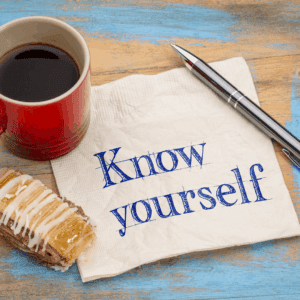

And so what he would say to people, that always stuck with me, was, “Don’t just think about your music. It’s not about that. It’s about you as a person. You got to make yourself a dope ass motherf#cker.”

He was like, look, I have a lot of interests that are unusual. I’m into Chinese philosophy and martial arts and cinema. And I have done a lot of reading and I’ve lived a life and I’ve had experiences and filtered them through unique prisms. And I have my own little cosmology that I’ve built based on all these things that I’ve been uniquely passionate about.

He would say to people, just go and figure out who you are and explore things and learn things and have experiences in your life to the point where you can look at yourself in the mirror and just say, “okay, I’m a dope ass motherf#cker. I’m a cool person in all these different ways.” Right?

And you know, that’s a constant journey for all of us. We’re all aspiring to what the RZA’s talking about there. But then he said, “then you’re going to be that cool motherf#cker when you’re walking your dog.”

You’re going to be that cool motherf#cker when you’re buying groceries at the grocery store, when you’re interacting with your friends and your family or whatever. And then, when you sit down to make beats or write screenplays, you’re going to be that cool, unique motherf#cker. And you’re going to create work that also is imbued with that same sort of vibe that you’ve now cultivated as a person.

And so he would just say, “you guys are asking the wrong question. It’s not about how can I do what you do?”

It’s like people who hear about a great artist, and they’re like, what kind of a pen does he use? What kind of a brush does he use? That’s not the secret. That’s not where the secret sauce is. You can give a great artist a #2 pencil, and they could draw you a masterpiece.

It’s the same thing with a screenwriter or a hip hop producer. And I think it kind of speaks to what you were saying. You have to cultivate yourself as a person.

And I think that might sound scary or intimidating to people, particularly if someone’s younger, but it shouldn’t be, because that should be the journey that you want to be on: to make yourself a more interesting person.

And then, by osmosis, that can’t help but come out in the work.

Sometimes, people think the work is so separate, that it’s this other thing outside of themselves, like you can be a person outside of your work, and you’re not connected to it. But, like you said, then you’re not doing it right.

You have to have this sort of feedback loop with your work.

I remember, I was asked by my old writing mentor, who taught at UCLA for many years, Tim Albaugh, who is a tremendous mentor to me and an amazing teacher. He asked me, and I was very touched, to be a guest speaker at his screenwriting class in the professionals program at UCLA a few years ago.

And so, I was sitting there talking to a bunch of screenwriting students, and I remember someone in the Q&A, one of the students asked me, “What is the piece of advice? Or what is the question that you think would be most helpful for us, for you to answer yourself right now that no one ever asks you?”

She was basically like, give yourself a Q and then give us the A!

And I said, “well, honestly, I’ll tell you guys, something. You’re probably not gonna want to do this, most of you, because you’re here at a very expensive film school. And probably, a lot of you think very highly of yourselves already. And so I’m just going to drop this little seed for you, hopefully, to look back on and maybe just a couple people in this class will take this seriously ten years from now…

None of you are as good as you think you are.

And it’s not a product of anything other than time and life and experience. And if you really want to get good, fast, the things that I know that are the fastest accelerants that will help you get to someplace meaningful as a writer: You should go fall in love, and have a serious relationship with somebody. Because you’re going to learn more about yourself in that process through that process than you could ever learn from a million screenwriting books or classes. Go fall in love.

And give yourself to someone. Sacrifice. Take a huge risk, open yourself up and be willing to be utterly obliterated, because you’ve given this other person that much power over you. Do that, have a relationship, fall in love. And then go find a therapist and go to therapy. Go talk about the stuff that you have never talked about. Really get to know yourself and examine yourself and find out why you are the person you are.

And give yourself to someone. Sacrifice. Take a huge risk, open yourself up and be willing to be utterly obliterated, because you’ve given this other person that much power over you. Do that, have a relationship, fall in love. And then go find a therapist and go to therapy. Go talk about the stuff that you have never talked about. Really get to know yourself and examine yourself and find out why you are the person you are.

And look back at your family, with an objective eye, through the eyes of a professional, and talk out why you have the issues you do.

Because if you don’t understand yourself as a person, how are you going to understand the characters you’re creating?

Without that, it’s like you’re writing in darkness. You don’t have a connection to why you are the way you are. And that doesn’t mean you get fixed overnight, or you become a perfectly healthy person overnight. Of course, that’s not what happens. But at least you cultivate awareness. And ideally, you get better and healthier and all that. But all that goes into your writing.

And I know for me, I spent a lot of my 30s in therapy, and I’ve been in therapy on and off for well over a decade. And for me, that was one of the things that helped my writing so much. And I never expected it, but it gave me a much deeper reservoir of understanding of people to draw from. It gave me a whole different framework. And I feel like, honestly, my stories got a lot deeper. I was thinking about things on a lot more levels. That was super valuable.

So yeah, so for what it’s worth, fall in love, find a therapist.

Jake: I’d love for you to talk a little bit about how your Workshop at the studio works.

Steve: Jake, you gave me this incredible opportunity. I think it’s been about a year now that I’ve been doing this bi-weekly writing Workshop at the school. We do it on Zoom. And I’m working with a small intimate group of writers. And I’ve basically run this Workshop precisely in the mold of my own writers group, which is one where there is no homework. Outside of the group, we have writers bring in a reasonable amount of pages, let’s say 10 pages or so, give or take, to every meeting. And we will do a quick table read of the pages from each writer.

And for those listening who are not familiar with what a table read is, it’s really simple. The writer basically just casts the other writers as actors in their piece. And then I will read the description. And we have this really quick, fun table read. And then we discuss it, we critique it. And I like to make sure that everyone says something during the critique, and you very quickly start to find out the commonalities of what’s working and what’s not. And for me, it is just so enormously helpful to get your work up on its feet, in front of a group of people. And it’s been an integral part of my process for the last two decades. And the times in my career where I thought I didn’t need the writers group, and I didn’t have one, were the times where I really fell off the rails in terms of productivity.

So with the group that I do with the school, it’s every two weeks, year round, like clockwork. We meet for three hours on Zoom. And I’ve been really heartened to see the progress of the writers I’m working with. I’ve got some amazing writers in the group, but they’re also just really cool people.

And anytime you have a writing workshop or writing group that meets regularly, it’s just as much a support group. Because being a writer, as you know, is very challenging at times. And it’s lonely, and it’s frustrating, and it’s heartbreaking. And it’s all these things that it’s hard to bear the weight of alone. But it makes it exponentially so much easier if you’ve got a cohort of people, your comrades, your peers, who you are now on this journey with. And so your successes and your failures are no longer just your own, they’re shared with the group, and vice versa. And so it’s really a cool thing. I lead the group, I moderate it. And we have a lot of fun. It’s a lot of laughter and a lot of jokes. And from the feedback I’ve gotten, everyone seems to be finding it super useful. And they’ve had I think, some of the most productive writing years of their life, because now they’ve got a deadline every two weeks, and they got an audience of their peers waiting for them. And that gives you a built in accountability as a screenwriter, which I think is invaluable.

Jake: Steven is very humble. But I’m going to talk about the role that he plays, because it’s so profound. It’s very rare to find a great teacher.

You guys don’t know this, but I put my teachers through hell before I hire them. Because it’s so rare to find somebody who can not only hold a writer’s work, but also hold the writer’s heart in their hand.

And that’s one of the things that I so admire about Steve. In his group, it’s not just about developing the writer’s story. It’s also about developing the writer.

And he’s just done such a beautiful job with this intimate group, helping them not only grow as writers but grow as artists, learn how to give feedback to each other that’s going to be the most valuable to each other’s scripts and careers, learn how to deal with feedback that you don’t know what to do with, have that mentorship when you’re stuck, when you’re going the wrong way, when the rewrite is not taking it to the next level. And the opportunity to have that kind of guidance from a person with Steve’s experience is really wonderful. And so that that’s one way of working with you. And the other way is ProTrack. And I wonder if you could talk a little bit about how ProTrack works.

Steve: ProTrack is another very unique thing that we do here at the Jacob Krueger Studio. Essentially, it’s a one-on-one mentorship program, where writers work directly with a single mentor. We meet up on Zoom, either every week, or every two weeks, whatever pace the writer would like to pursue. And we just talk out their story. They will send me pages prior to each meeting, and I will read those pages, make my notes, and then we’ll get on a Zoom call, and we’ll just kind of talk frankly, hopefully with encouragement and kindness, but also with bluntness.

That’s what I strive for, to have a balance, because I take it really seriously that someone is trying to improve and make their work better. And so it doesn’t suit anybody to approach the material with kid gloves. Nor does it suit anyone to be unkind or harsh about things. And so I always make a point of really celebrating what the writers I work with in ProTrack, or in my Workshop. I really take the time to celebrate what they’re doing well, because I think that’s something that some instructors might glide past too quickly. And I think it’s important to tell a writer what they’re good at. I like to focus on that, use that as a foundation, and then just say, look, no writer, professional or otherwise is great at everything. So here’s the stuff that I think you’ve got a real strength with, and honestly, here’s the stuff, here are the elements, that I think you could use some work.

And then we talk about it in granular detail. I think the people that I work with would tell you I drive them nuts in terms of how much I nitpick the tiniest little things, and it’s because I really believe all that is super important. So from the macro to the micro in ProTrack, the cool thing is we have a lot of time together.

I get invested in people’s stories, and I don’t want to get off a Zoom call until I feel like we’ve solved the problem, or we’ve got to a point where they’ve got a new angle on how to approach something. And so it’s been really rewarding. I love working with writers.

There are some writers I’ve been working with now, through ProTrack, for the whole time that I’ve been working at your school. I’ve had some people with me forever. And it’s really rewarding to watch their careers start to blossom, as they start to get meetings with managers and agents, and they’ll send me emails like “Steve, oh my God, look, who wrote to me! The script that we developed, all these managers love it!”

There are some writers I’ve been working with now, through ProTrack, for the whole time that I’ve been working at your school. I’ve had some people with me forever. And it’s really rewarding to watch their careers start to blossom, as they start to get meetings with managers and agents, and they’ll send me emails like “Steve, oh my God, look, who wrote to me! The script that we developed, all these managers love it!”

And it’s cool. It reminds me of just how exciting that is, to have those first moments in your career.

So it’s really fun. But I also just don’t want people wasting their time. So I try really hard to push the writers that I work with, as hard as they’re willing to be pushed.

Jake: The ProTrack program is really our answer to grad school here at the studio. I have such an issue with the film schools.I think they have good intentions, but I think their programs are backwards. Because you get two years of bliss, three years of bliss, where all you do is write, and then you graduate with $300,000 of debt, which makes it impossible to be a writer.

And then on top of that, not only do you have the debt, but you don’t have the mentorship anymore. Now you’re out in the world, and you’re trying to make it and you don’t have anyone to talk to, and maybe you find a writers group, and you can hope that they’re good, but maybe they’re not. And in the best case scenario, you want to be learning from people who know more than you do!

So, the idea of ProTrack and the idea of The Workshop, is different writers learn best in different ways. Some people like one-on-one. Some people like to learn in a group. Some people do a mixture of the two. But the goal is to give you lifelong mentorship, where at the beginning you might be talking about “what’s a character?” But five years later, you’re talking about “Okay, my agent gave me this note and I don’t know what to do, or my showrunner has a different opinion than the network, and I don’t know which one to listen to!”

As you emerge in your career, you have that mentorship for life. Because I know I am who I am because of the mentorship I received. Just as you spoke about how you are who you are because of the mentorship you received.

And what’s really beautiful about the program is that, to say it’s a tiny fraction of the cost of grad school doesn’t even cover it. You could study with Steve at UCLA and spend 60 grand a year, or you could study with him here, and spend as little as $350 a month.

And so it’s just a really wonderful opportunity for people who are really serious about their careers to experience these programs and figure out how to move forward with that kind of mentorship. And I’m just so happy and grateful that you are a part of our school, and that I get to work with you.

So thank you, Steve. Thank you for your time and for opening yourself up in this way for us.

Steve: Thank you so much, Jake. This has been lovely. I always love talking about screenwriting and it’s always a pleasure to chit chat with you, so thank you very much. I had a blast.

Want to learn more? Come check out our FREE Quarantinis Happy Hour every Thursday night, where a Jacob Krueger Faculty Member and I go deep on some aspect of screenwriting, answer questions, and share feedback and writing exercises. Take the next step and sign up for one of our online Screenwriting, TV Writing, Playwriting or Comics Writing classes. Or give yourself a film school level experience at a tiny fraction of the price and on a schedule that fits your real world life with our professional level Protrack and Workshop programs.

Edited for length and clarity