Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom: The Art of Adaptation

This week, we’re going to be looking at Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom, by August Wilson, adaptation by Ruben Santiago-Hudson.

I’m so excited to talk about this script, not just because it’s a great movie, but because it’s one of the great plays of all time. So that means, this episode, we get to talk about the link between playwriting and screenwriting, the similarities and the differences.

And more importantly, it means we can talk about the art of adaptation.

If you’re a screenwriter or TV writer, at some point in your career, you’re going to do an adaptation, which means, just like the writer of Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom, you need the skills to know how to adapt a play, novel, memoir, short story, true story…heck even a board game into a movie or TV show.

If you look at what’s happening in the industry right now, most of the work-for-hire projects are based on something called IP, intellectual property. We’re taking this thing that is not yet a movie, and we’re translating it into something that is a movie or TV show.

I want you to focus on that word translation. An adaptation is not a copying of the plot. An adaptation is a translation of something that was written in one language into a different language.

And the art of adaptation is challenging, because as screenwriters, as writers we want to honor the work of the artists that we are adapting.

Even if you’re doing something crazy, like adapting an amusement park ride like Pirates of the Caribbean, you want to honor what’s great about that ride. If you’re adapting The Lego Movie, you want to honor what’s great about Legos. And if you’re adapting a play, you want to honor what’s great about the play.

And honoring what’s great about the play, or the movie, or the video game, or the book, or the memoir, or the torn from the headline story, or your personal life story, or the dream you had last night… or even adapting the rough draft of your script. When you’re doing this act of adaptation, you’re translating something from one form to another.

And that means that you may not get all the literal details. Because the literal details were created for a different form. But what you’re trying to capture is the intent.

The first question you want to ask yourself whenever you’re working on an adaptation is: do I trust this material?

Do I trust this writer? Do I believe in this material? Do I generally like the project?

Do I trust this writer? Do I believe in this material? Do I generally like the project?

And that doesn’t mean is the project good or not? It means does it resonate for you? Does it matter to you? And if it doesn’t all resonate for you, you want to ask yourself, Well, what part of it does? What part of it do I really, really, really connect to?

If you think about The Lego Movie, Chris Miller and Phil Lord, my friends who adapted it, connected to this idea of playing by the rules, and also playing in your own way, right? That was the piece of Legos that connected them in a personal way. How do you express yourself, when “everything is awesome,” and playing within the rules makes everything awesome, but you also want to be a wild artist and do your own thing.

They took that one idea about Legos and they built around it. They decided they trusted the material, found the thing they connected to about it, and built around that.

If you look at The Reader by David Hare, that’s an adaptation of a book that is not very successful in its own right. The book is written by a lawyer and it’s focused on the ins and outs of Nuremberg law. And underneath all the not-so-exciting details is this really complicated story about a little boy, who’s in love with a woman who turns out to be a Nazi. She comes back into his life, later in life, and he has to deal with the fact that he loves her, even though she was a Nazi.

And it’s very interesting, because when you look at David Hare’s adaptation of The Reader, he basically threw out almost everything about the book. He decided he didn’t trust the material. So instead, he just kept this one idea, this one little piece, this story that the writer almost overlooked.

So you want to ask yourself, does the whole piece work for me? Is there just a part of it that works for me? What resonates? What matters to me?

What matters to you when adapting a project like Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom might be different than what matters to somebody else. In fact, it’s important that it does, because what matters to you will become your take on the project. The way you pitch yourself to write the project that actually gets you the gig.

Your take is really just a way of saying during your pitch, “this is what matters to me. This is what I’m going to build around”

And then every choice that you make as you adapt happens in service of that take.

So if you’re working on one of the greatest plays of all time, and you’re adapting it into a screenplay or into a TV show, you want to honor that writer’s take to the greatest degree that you can, you want to honor the choices that the writer made because they were probably smart choices. Because you connected to and resonated with them, you want to take those choices and you want to translate them as best you can into this new form.

And you don’t want to get hung up on the things that you didn’t resonate with. Because those things don’t matter so much to you. You don’t have to worry about translating every plot point, you have to worry about translating the essence.

For another example of this, you could look at a movie like Let the Right One In, which is a fabulous little vampire movie.

Let the Right One In is adapted from a gigantic novel, telling the story of a 13 year old vampire. And it’s super complicated and super long. And in adapting his own novel, not surprisingly John Ajvide Lindqvist quite liked the novel and resonated with the novel. But the novel was too darn big to be a movie. So what the writer did was take the part of that story that represented the whole, the part where the vampire is looking for a new little boy to take care of her, and focus on translating that, even though it meant letting go of vast swaths of plot he’d worked really hard on.

Now that you understand how to think about adaptation, we’re going to dissect the adaptation of Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom, exploring both what worked in that adaptation, what made the movie better, and also what didn’t work, what got in the way of that adaptation.

There’s a popular idea about adapting a play that I don’t totally agree with (like most of the common wisdom about screenwriting), the idea that when you translate a play into a feature film, that you need to “open it up.”

In plays, we have this concept called Unity of Place. There’s this one specific world that we’re building, within the four walls of the stage and the theatre. In fact, if you have studied with Lisa D’amour, our wonderful playwriting mentor (she’s Pulitzer Prize finalist, and used to run the theater MFA program at Brown, so check out her class), Lisa talks all the time about world building, because so much of theater is about building that world. You have this one place where the story takes place.

Theater is similar to television in this concept of Unity of Place, which might be one of the reasons why so many playwrights make that transition into television writing, and why agents and managers look to the playwriting world to find new TV writers.

TV writers are world builders because they have to be. Because they’re constrained by the limits of a single stage. And in a sense, TV writers have to think in the same way. Though there may be more locations than a single stage, the show will tend to come back to the same handful of locations again, and again and again.

But even TV is more complicated in the way it builds world, because you don’t have this one place, this Unity of Place in the production. You have all these places, you have lots and lots and lots of places. And when you get to feature films, it gets even bigger, right? You have so many different places.

And the power that we have in feature films is the power of the cut. Cutting from one place to another in order to tell the story, cutting from one image to another in order to tell the story.

Whereas the most powerful tool that we have in theater is entrances and exits, coming in or out of a scene, in or out of that unified place, because that’s how you shift the power dynamic in a theatrical production.

So there’s this idea that a play is built to happen in one space, with characters talking to each other over long periods of time, and the power dynamic shifting as characters enter and exit. That’s how they’re built. While movies, in general, are built around the power of the cut.

Which leads to the common wisdom, which, again, I disagree with, that if you’re gonna adapt a play into a film, you got to “open it up,” and try to create as many different locations as possible so we don’t feel claustrophobic in this one little world.

Like most rules, the common wisdom that a movie in a single location cannot work is, of course, not true. For example, look at a successful horror movie like Saw, that literally takes place in one room. Look at the parts of Doubt that worked best, which are not the parts that they “opened up,” but the parts where they allowed the characters to talk to each other.

And look at the parts of Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom that worked best. It’s not the parts that “opened it up.” It’s the parts where they allowed the characters to talk to each other.

So why is this rule of thumb so utterly unimportant? Because in general, Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom works. Because it’s a well constructed play– not just a well constructed play, one of the best constructed plays, one of the best plays ever written. And that’s not me saying that, this is a Tony Award winning play.

When you’re adapting material of this quality, to the degree you can, you want to honor the intentions of that writer. The play is built around those intentions, that world, and those locations.

In fact, if you read the play, what you will see is that the play is set in two locations. It is set in an upper location, which is the recording studio. And it is set in a lower location, which is the band room.

That didn’t happen by accident. In Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom, August Wilson was building a world. And the world he’s building is constructed around the socio-economic and racial disparities in our society.

So you have the rehearsal room, where you have the white men on top in the booth. And they’re the ones with the real power. But then you have Ma Rainey, the Black star, struggling to hold on to her own power in relation to, and over the white men up there in the sound booth. She’s built on a real person. There really was a Ma Rainey, although these events are fictional.

So you have the rehearsal room, where you have the white men on top in the booth. And they’re the ones with the real power. But then you have Ma Rainey, the Black star, struggling to hold on to her own power in relation to, and over the white men up there in the sound booth. She’s built on a real person. There really was a Ma Rainey, although these events are fictional.

So it’s built around Ma Rainey. And in this play, August Wilson is doing his own fictional adaptation of her life.

August Wilson’s take on Ma Rainey sees her as a Black woman at the pinnacle of fame, who seems to have transcended the racial inequalities and she has risen to the top, but who knows how fragile her grip on power is, and how it will be taken from her the moment she lets down her guard.

And then, down below her, you have the band, way down below in the band room.

So there’s a real song called Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom. But metaphorically, the band is also Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom.

The band is an echelon below Ma Rainey and they do not have the power.

The young girl, Dussie May, whom Ma Rainey’s got her eye on, who doesn’t even have the power to determine who she’s interested in or where she wants to go.

The stuttering Sylvester, whose fate is decided by Ma Rainey, whether or not she’s willing to fight for him, and who can only earn a living or a positive view of himself through her insistence on his behalf.

The incredibly talented Levee, played so brilliantly by Chadwick Boseman, who’s really the future of music, but who is held down by Ma Rainey’s rules, and by all the other guys in the band who don’t believe in him.

And all the other members of the band, Slow Drag, Toledo and Cutler, who are all the servant class to the wealthy, powerful Black woman, Ma Rainey, who is also struggling, just like the they are, not to be pushed down further, who is fighting not to be the servant class to the white men up in the booth.

This is the world that August Wilson has built. And it’s built around these two playing spaces, one up high, and one down low. It’s built around that world. That’s the architecture of the play.

So the degree to which you honor that architecture, the adaptation is going to be successful.

In the best adaptations, what you’re actually going to do is take the elements that could not be done in a play, that could only be done in a film, and figure out how to amplify those elements.

In this case since the play is built around that world, you want to amplify that world. You don’t want to open it up. You want to turn up the volume on the differentiation between high and low.

And that statement that August Wilson is trying to make about power and race, the same conflicts that he’s capturing back then, those issues we’re still wrestling with today. If you really want to do a great adaptation, what you want to do is you want to push them even further by using the power of film to do the things that it can do that playwriting can’t do.

Similarly, if you’re writing a play, you want to take the things, that theatricality, that film writing can’t do and you want to do it in the play.

There are moments in this adaptation, where Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom succeeds in making the film do things that the play cannot do. But there are other moments, and I’m sure you felt them, where you can feel the play being opened up whether it serves those themes or not.

You can feel those moments when the writer is “opening up” the locations not because it serves the theme of what he’s building, but because it serves the rules of what they’re supposed to do in a screenplay.

The first time you see this is actually the opening shot. And don’t get me wrong, it’s a beautiful shot, right? You’re watching these young Black girls running through the forest. And it feels a little bit dangerous. And then you see fire. And then you see them come up to a tent where Ma Rainey is performing. And then we cut and we see Ma Rainey performing in the city. And we realize, “wow, she’s really made it.” She’s transcended! And we get this story of the birth of the blues. And she’s the mother of the blues, right?

So we see all that, and it’s fabulous filmmaking, but it doesn’t actually serve the story, at least not the way I see it.

The reason it doesn’t fully serve the story is that this story is actually not Ma Rainey’s story. This is actually the story of Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom.

This is actually the story about how shit flows downhill. How under the oppression of an unfair society, where wealth and power are unevenly distributed, how shit flows downhill, down to that servant class band, in the underground band room.

It’s about how, instead of striving to “make the world a better place for other Black men,” the characters in the play end up turning against each other, fighting each other, rather than fighting the real cause of their suffering.

And of course, because it’s a great play, it does it in a complicated way, right? It’s not pointing fingers and saying “you’re bad, and you’re good.” It’s a complicated portrait.

We understand why Ma Rainey’s acting the way she does, even though she’s acting like a primadonna.

We understand that there is a part of Sturdyvant that really, really likes Levee’s music and really wants to do something with it. And we also understand that there’s a part of him that knows that if he’s got to choose between the new young talent and Ma Rainey, his big, expensive act, he’s gonna choose Ma.

We understand how each of these characters are human, inside this human dilemma.

And we even understand (without ruining it, for any of you who haven’t seen it) why Levee makes the final, destructive choice that he makes.

We understand how the unfairness, the pressure, the exploitation, the divisions between wealth and class, not only among white and Black, but even inside the Black community, create this powder keg of violence, where the people who are suffering most end up turning against each other. That’s Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom.

That is the story that August Wilson is telling.

So when you go back to that opening sequence, you can see, though the filmmaking is beautiful, and even though yes, it succeeds in “opening it up,” those scenes don’t power the story, because they put our focus on Ma Rainey’s success, rather than on the powder keg of the band below her.

Whereas, if you look at the way the play is built, if you honor the choices of the writer, you will see that Ma Rainey doesn’t enter into the equation until Ma Rainey enters. And it’s not at the beginning of the play.

Because the play is not about Ma Rainey. Because it’s about Levee. Because it’s about the boys in the band. Because it’s about those guys underground in that band room, not the guys at the top.

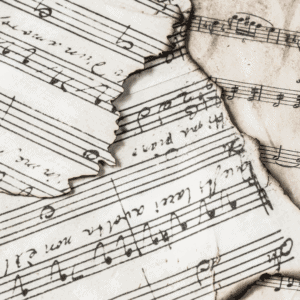

I’m going to read you a section from August Wilson’s introduction to the play, Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom, and I think you’re really going to enjoy this, because this introduction describes what August Wilson wants you to feel, but it’s all stuff he actually can’t make you feel in a play.

Here’s what he wrote:

THE PLAY:

It’s early March in Chicago in 1927. There’s a bit of a chill in the air. Winter has broken out but the wind coming off the lake does not carry the promise of spring. The people of the city are bundled and brisk in their defense against such misfortunes as the weather and the business of the city proceeds largely undisturbed.

Chicago in 1927 is a rough city, a bruising city, a city of millionaires and derelicts, gangsters and roughhouse dandies, whores and Irish grandmothers who move through the streets, fingering long black rosaries. Somewhere a man is wrestling with the taste of a woman in his cheek. Somewhere a dog is barking. Somewhere the moon has fallen through a window and broken into 30 pieces of silver.

It is one o’clock in the afternoon. Secretaries are returning from their lunch. The new mass at St. Anthony’s is over and the priest is mumbling over his vestments while the altar boys practice in Latin. The procession of cattle cars through the stockyards continues unabated. The busboys in Mac’s Place are cleaning away the last of the corned beef and cabbage, and on the city’s Southside, sleepy eyed negros move lazy towards their small cold water flats and rented rooms to await the onslaught of night, which will find them crowded in the bars and juke joints both dazed and dazzling in their rapport with life. It is with these Negroes that our concern lies most heavily: their values, their attitudes, and particularly their music.

It is hard to define this music. Suffice it to say that it is music that breathes and touches. That connects. That is in itself a way of being, separate and distinct from any other. This music is called the blues. Whether this music came from Alabama or Mississippi or other parts of the South doesn’t matter anymore. The men and women who make this music have learned it from the narrow crooked streets of East St. Louis, or the streets of city’s Southside, and the Alabama or Mississippi routes have been strangled by the northern manners and customs of free men of definite and sincere worth, men for whom this music often lies at the forefront of their conscience and concerns. Thus they are laid open to be consumed by it; it’s warmth and redress, its braggadocio and roughly poignant comments, its vision and prayer, which would instruct and allow them to reconnect, to reassemble and gird up for the next battle in which they would be both victim and the ten thousand slain.

August Wilson writes all that in a section before the play starts, about the play, and of course, that’s the part that you actually can’t create on the stage.

If I was trying to find a new first scene that “opened up” Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom, I would “yes… and” that little piece that August Wilson wrote about the play. I would dramatize that in my adaptation.

And you can see how the focus would be different, right? The focus is not on the stars, it’s not on the power, it’s not on the rise to fame, it’s not even on the blues. The focus is on those men at the bottom. And it is particularly on those men, right? The focus is on those lower class people, slaving away trying to survive.

And that’s not to say that you couldn’t do a feminist reinterpretation on Ma Rainey– that you couldn’t ask the question “why shouldn’t the mother of the blues be the star of her own play? Why does the focus have to be on the men?” If you doubted the material, or saw that as a hole in it, there’s nothing wrong with coming up with a new take.

But if you make that decision, you have to recognize that changes everything– because you’re now building a new structure. You can’t just pop back to the old one, or the two pieces won’t fit together.

What’s amazing as you read August Wilson’s statement is that you can immediately see all the shots that could have been used to “open this piece up” in film form. August Wilson is already giving it to you. He knows where he wants the focus to be– he just doesn’t have the camera to show it.

So if you trust the material, and want to honor his intentions, you’ve got to tip the camera downwards to the people in the basement, the servant class, rather than up there at the upper class.

When you’re adapting a great playwright, when you’re adapting a great piece of material, to the greatest extent that you can, you want to “yes… and” what’s working.

If you’ve got to open it up, because a producer says “open it up,” then open it up by “yes… and-ing” what already is there.

Don’t take your focus and put it on something that’s not the focus. Always build out of your theme.

You might have noticed that some of the other attempts to open up the screenplay also caused some other problems downstream, little weird holes in logic that exist in the screenplay that are completely absent from the play.

For example, they try to “open up” the script by writing Ma Rainey’s car crash as an “action sequence.”

Early in the piece, Ma Rainey gets in a tiny little car accident, a little fender bender. And she has a confrontation with a policeman, which gets settled up for her by Irvin, her manager, who then hustles her into the music studio.

In the play, all this all happens in exposition in the recording studio during Ma Rainey’s big entrance.

In the film, they try to open it up by having it take place live in the street.

The only problem, in the play, it totally makes sense awhile later when Ma says “go fetch me my car,” because you understand that the accident happened way earlier, and the car has been in the shop for some time before Ma even arrived.

Whereas, when you just watch the accident happen outside, sure it opens up the script. But later, when she demands the car to be fetched you wonder, “what the heck is she talking about? Get the car from the shop? It crashed like five minutes ago!”

Again, by trying to “open up” the play simply for opening up’s sake, rather than “yes… and-ing” the internal infrastructure of the play, they end up losing some of the internal logic of the piece, without adding much at all to the story. Because a few minutes later, we’re going to lock ourselves in those rooms, and for the most part, from that point on, we’re closed down to those locations, one way or another.

All these changes are made for very little gain. Because the piece is not about Ma Rainey’s accident. The piece is about the boys in the band, tearing each other apart, because they can’t see any path to claw their way upward.

The next place they try to open it up is when Levee goes to buy his shoes. And this is a less problematic choice, because at least we’re focused on the main character, and his desire to find his way to a higher place in society.

In fact, there’s a way to effectively build the adaptation this way, if you really have to open it up. Because the symbol of those shoes, and Levee’s need to buy them, is ultimately the thing that’s going to lead to the tragic ending.

So if you start there, and then cut to Ma at the fancy hotel, playing her “I’m a powerful woman” game, with her new hot young thing on her arm, there is a way to open it up with those two scenes, without distracting from the real theme.

Those two scenes do help us understand the power dynamic, the character striving for more power, and the character who is striving to show everybody that she has arrived.

That said, neither of those scenes add that much to the adaptation. Because when does the movie really start? The piece really starts when we get the band into that room, we allow them to start talking to each other. It really starts exactly where it starts in the play. When Levee shows up with his brand new shoes, in his brand new shoe box, when Toledo steps on his shoe, for the very first time, that’s where the piece really starts.

And anything you add before that moment where Levee shows up all full of excitement, and Toledo steps on his shoe for the first time risks diluting the powerful ending we’re building to, by pointing the audience’s attention to all the shiny stuff that looks pretty, rather than to the structural bones on which the play is built.

So, I want you to be careful of “opening things up” to play by the rules. I want you to be careful of playing by the rules for the rules’ sake at any time.

Don’t “open things up” to play by the rules, “open things up” to amplify your theme.

If you end up thinking that yes, actually seeing Ma Rainey at the hotel does amplify your theme, then great, let her make that entrance.

If you end up feeling that having Levee buy those shoes on camera amplifies your theme, by all means let that scene happen.

But don’t create random girls running through the woods, as beautiful as those shots may be.

Don’t take the focus and put it on the woman in power when the story is built around the men in the basement.

Despite the places where “opening up” the adaptation of Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom, didn’t work, there are other scenes where the opening up of this script is truly brilliant.

In the play, as in the movie, there is a new door in the band room that Levee doesn’t remember, that he keeps on pointing out. And in the film, he is constantly playing around with that handle, unable to open that darn door.

In the play, as in the movie, there is a new door in the band room that Levee doesn’t remember, that he keeps on pointing out. And in the film, he is constantly playing around with that handle, unable to open that darn door.

So we’re down in the band room underground with Levee, and the door becomes a symbol of being trapped underground, and his desire to open that door is a metaphor for his desire to ascend, to transcend, to be up there at the top, to own his gift and let it be heard.

In the play, there’s a limit to what you can do with that door. A door is a door. And all it can do is open or close to another part of the stage.

But in the film, the filmmakers use the image of that door to amplify that symbol, to “yes… and” August Wilson’s metaphor, to make the movie do something that you couldn’t do on the stage.

In the movie, there’s a moment when Levee finally goes through the door. This moment doesn’t happen in the play, because it can’t happen in a way that we could understand. But in the movie, he finally breaks through, and the camera can go with him.

And together with Levee, we experience the devastation of realizing the door doesn’t lead anywhere.

The door leads to a giant column of bricks that surrounds him on all sides and extends up into the air.

Now, that’s how you adapt a play into a film.

You can’t get that shot in a play, because you can’t see it. But using the power of film, you can amplify August Wilson’s image, you can “yes… and” it, you can take it to the next level.

The next place that I’d like to talk about (and there are going to be some spoilers at this point. So prepare yourself…)

Levee thinks he knows what’s going to happen at the end of this story. He knows it. We know it. Even the producer knows it. And while the band might not want to know it, and Ma might pretend to be oblivious together, everybody knows that Levee is the future of music. And Ma is the past.

Levee’s got the new thing that everybody wants. And the other servant class characters, the band members, who feel just lucky to have a job, are doing their best to hold Levee down and keep him just playing the songs the way they’re written, the way that Ma wants them, the way that doesn’t the rock boat and doesn’t lead to anywhere new, the way that protects you from getting yourself fired and really having nothing.

But Levee wants to transcend all that, and Levee knows he’s got something that other people don’t have. And Sturdyvant, the producer, knows where the future is leading, and has even asked Levee to write up some of those songs. And he’s promised Levee he’s going to record them.

So Levee has gotten a taste of the future, when he won’t be on the bottom, but on the top. And he wants that more than anything. In fact, that’s why he bought those shoes. He’s gotten the taste of a future where he’s somebody.

And despite his very, very complicated relationship with the white man, given the violence he’s suffered and the rape of his mother, when Sturdyvant comes in, Levee puts all that behind him and immediately starts “dancing.”

We watch Levee want what Sturdyvant has to offer so badly he’s willing to even betray himself.

And even as he strains toward that desire, he’s being held down by his own people, and he’s being held down by Ma, who doesn’t want to lose her place that she fought so hard for. And Ma knows well just how easily it can all be taken away from her.

And by the end of the piece, Levee has been fired by Ma. And Sturdyvant doesn’t want to let him record his songs anymore. Why? Because he doesn’t want to lose Ma Rainey as a client. Because Ma is a sure thing, and Levee is a risk. And it was one thing to record the songs of a guy who played for Ma, but it’s a whole different one to record the songs once Ma has fired him.

doesn’t want to lose Ma Rainey as a client. Because Ma is a sure thing, and Levee is a risk. And it was one thing to record the songs of a guy who played for Ma, but it’s a whole different one to record the songs once Ma has fired him.

So instead of recording the songs, Sturdyvant buys them off of Levee, for five bucks a song. And all of Levee’s dreams are utterly destroyed.

And then, tragically, for the second time Toledo steps on that shoe.

And this time, Levee loses it. And rather than striking out at the real power, the real people who have hurt him, he strikes out at the guy who’s just one rung above him, for ruining his new shoe. He strikes out at Toledo, because the real power that’s oppressing him is, quite frankly, too complicated to even wrap his head around.

And of course, we see the same problems playing out in our politics, and in our society today.

August Wilson’s talking about something really, really real here.

In the play version of Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom, that’s where the story ends. Because that’s where it has to end. But in the adaptation, the filmmakers are able to use the power of the cut to take it one level further.

In the movie, we cut, and we see a white singer singing Levee’s song. And accompanying him is not a little band like Ma Rainey’s little band of Black men, for whom they don’t even want to turn on the air conditioning, for whom even that one extra mic is too expensive…it’s a big band, with a conductor. And they’re all behaving exactly the way that the manager would like them to behave, and there is that young, handsome white singer who is singing Levee’s song with all the production values neither Ma nor Levee will ever have.

In a play, you couldn’t have a last image like this, because doing it would require a level of casting that would be unaffordable. You’d have to pay a dozen actors to sit around for two hours backstage, just to create a 30 second moment at the end of the show.

But in a film, it’s just an extra day of shooting.

By creating that new final image in this way, what the filmmakers are doing is taking August Wilson’s message, and translating it, adapting it, amplifying and transforming it using the power of film.

So we get one more beat, and the story becomes not just about what was taken from Levee, but what was taken from the Black community.

We dramatically experience the way that Black music was appropriated by white culture, and how much was lost along the way.

And we don’t see it in a simple way. We don’t see it in a pointing fingers way. Or a way that pretends that no white singer should ever sing a Black song.

We see it in the complex, messy way that it really happened, and continues to happen, in a world where power isn’t doled out equally.

And you can see that this final image is actually a “yes… and” to that last paragraph in August Wilson’s statement about the play. The statements that he knows you’re never going to experience in the theater.

The men and women who make this music have learned it from the narrow crooked streets of East St. Louis, or the streets of city’s Southside, and the Alabama or Mississippi routes have been strangled by the northern manners and customs of free men of definite and sincere worth, men for whom this music often lies at the forefront of their conscience and concerns. Thus they are laid open to be consumed by it; it’s warmth and redress, its braggadocio and roughly poignant comments, its vision and prayer, which would instruct and allow them to reconnect, to reassemble and gird up for the next battle in which they would be both victim and the ten thousand slain.

This is the power of translation. This is the power of adaptation. This is the power of film.

So, when you’re adapting your own work, whether it’s a novel, a short film, a comic book, a memoir, an article, a board game, a true life story… even if it’s an adaptation of a rough draft of your own script, something that’s not yet a movie, but wants to be…I want you to remember where to put your focus.

And similarly, if you’re going the other way, if you’re writing a play, if you’re writing a comic book, if you’re writing a novel based on a film, I want you to remember where to put your focus.

The first question you ask yourself is how much do you trust this author?

If you trust this author, you want to honor their choices, you want to try to build, to the extent you can, in the same way they built.

If you don’t trust this author, you want to ask yourself, what is the part of this material that I do connect to?

As you’re adapting you want to ask yourself: “What’s my take? What is the thing in this that matters most to me, that I think is the central theme that they’re building around that resonates with me.”

You want to make that your focus.

And then as you do this act of translation from one form to another, please don’t follow a bunch of rules. Don’t follow a formula, don’t follow what they’re telling you that you “should” do.

Instead, ask yourself, “how can I use this new form to amplify that theme? How can I use the power of cinema or the power of the stage or the power of a novel, not to replicate, but rather to translate, not to “open up” or “close down,” but rather to enhance and amplify the central idea, the central character, the central journey of the piece.

For all the ways that it both succeeds and fails, Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom is a film that you need to see.

It’s a piece that you need to see, because it shows you the power of putting two people in a room and letting them talk. Because it shows you the power of the written word.

And as you watch Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom, notice all the frantic ways they try to open up the film, and just imagine if the whole thing just took place in those two rooms.

Ask yourself, “if they hadn’t opened this up at all, would it have lessened your enjoyment?”

And I think you will notice, when you do that, how unimportant these rules that we get fixated on actually are.

Yes, a lot of movies use a lot of cuts. Yes, a lot of plays have Unity of Place. But these are conventions and tools, not rules. And all of these conventions and tools are really built to serve a theme.

Because in writing, form is function. What you’re trying to say, and the way that you want to build it, actually go hand in hand.

So go build something beautiful.

Want to learn more? Come check out our FREE Quarantinis Happy Hour every Thursday night, where a Jacob Krueger Faculty Member and I go deep on some aspect of screenwriting, answer questions, and share feedback and writing exercises. Take the next step and sign up for one of our online Screenwriting, TV Writing, Playwriting or Comics Writing classes. Or give yourself a film school level experience at a tiny fraction of the price and on a schedule that fits your real world life with our professional level Protrack and Workshop programs.

Edited for length and clarity