Dream Scenario: Passive Main Characters

This week, we are going to be talking about the new Nicolas Cage movie, Dream Scenario, by writer and director Kristoffer Borgli. This will be a fascinating discussion, because we’re going to talk about the strength of the screenplay, as well as the screenplay’s weaknesses.

We’ll use the strengths and weaknesses of Dream Scenario’s screenplay to understand one of the most important concepts in screenwriting: the difference between writing passive and active main characters.

Most screenwriters think their characters are active. But the truth is, we’re often writing passive main characters without realizing why the character is coming out passive. So that’s what we’re going to be looking at here: how to recognize if your main character is a passive main character or an active one.

We’ll look at the effects of a passive main character: what that does to your movie and to your audience. And we’ll look at some ways to transform passive main characters into active ones.

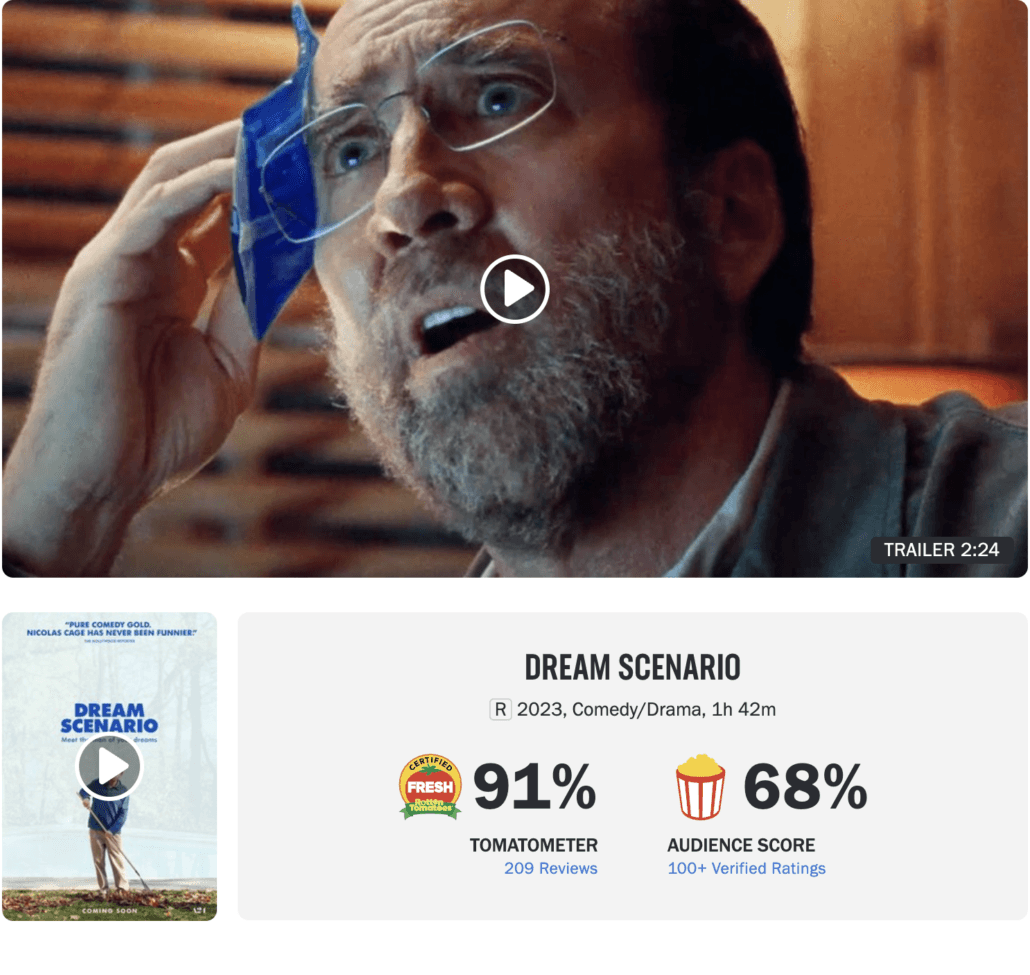

If you look at the Rotten Tomatoes TomatoMeter scores for Dream Scenario, you’ll see something that rarely happens – critics loved this film and audiences really didn’t.

It’s quite common to see critics dislike a film that audiences loved but here the exact opposite happened. Among critics, 91% loved this film but only 68% of the audience liked Dream Scenario.

Now, that is a really interesting phenomenon. So let’s look at why this might be happening.

If you look at the overall concept for Dream Scenario, it is totally fascinating. And this is part of the reason the critics love it. Sociologically, politically, this film is taking on some huge concepts and saying some really interesting things.

And quite frankly, from a Hollywood perspective, this Dream Scenario also has a really interesting hook and a really clear execution of that hook.

Not only that, it has a really stellar cast in Nicholas Cage, Julianne Nicholson and Michael Cera. It’s well directed. It’s well performed. And it’s fascinating.

So why aren’t audiences connecting with Dream Scenario the way that critics are?

Simply put, critics look at movies differently than audiences.

If you’re a screenwriter or you’ve studied screenwriting, in college or in grad school, or even if you’ve just read books about screenwriting, there’s a really good chance that those books are written by professors. They’re written by critics. And critics look at films in a different way than audiences (and producers) do.

The things that are actually important for the success of your film may be different than the things that are important for the critics to love it. That doesn’t mean you can’t do all the things that the critics love. Sure, if you want to make a really fascinating, critically acclaimed, complicated film that asks some really big questions about the world, yes, absolutely do that.

But you also have to make sure your craft is perfect. And there’s a tiny little craft issue in Dream Scenario that’s getting in the way. So let’s talk a little bit about it.

Spoiler alert: There are going to be some major spoilers ahead as we discuss the structure of Dream Scenario.

Dream Scenario is looking at one of the primary socio-political problems of our day: the desire for fame and the effects of that on our society.

To go even deeper, Dream Scenario is exploring the effects of the desire for fame for fame’s sake, rather than for having accomplished something or done something or created something.

It’s looking at the social phenomena of people just going viral and suddenly becoming the most interesting person in the world without actually having done anything to earn it. It’s looking at the sociopolitical, emotional and psychological fallout of that phenomenon, through the character of Paul Matthews, played by Nicolas Cage.

Paul Matthews is potentially the most boring man in the world. He is saccharin sweet, but a little too much. He has very interesting theories about biology. In fact, he is a tenured professor. But he’s never actually sat down and written his book– the one he conceived back in grad school. He hasn’t actually done anything in his life.

We first meet him in a really fascinating way. In the very first image of the movie, he is in his daughter’s dream. And really weird stuff is happening. Things are falling from the sky, and he’s just not doing anything. He’s just kind of standing there, raking leaves, while all this crazy stuff is happening around him.

When his daughter reports her dream the next morning, we start to see the insecurity of this character. He’s upset because he’s not doing anything in his daughter’s dream. He wishes his daughter would dream of him in a more active way, where he’s actually reacting.

Of course, that’s a reflection of his genuine insecurity, of his wanting to be meaningful, but it’s also a reflection of him not wanting to see his own character, psychologically. Because the character he is in his daughter’s dream is the character he is in the world. He’s a guy who’s not pursuing anything.

Paul Matthews, Nicolas Cage’s character in Dream Scenario, is a passive main character in his own life. And that makes him both a fascinating character, and also an extremely challenging character to write.

As a writer you’ve probably had that experience of wondering if you’re a passive main character in your own life. Because just the nature of the beast of being a writer is that we have more ideas that we can express in a lifetime, more stories than we can tell in a lifetime.

Like Paul Matthews in Dream Scenario, we have stories that we desperately want to tell. And a lot of us have internal blocks and questions we don’t want to look at:

Did I squander my talent? Did I wait too long? Have I not pursued it with the full strength of my being? Have I not gone for it?

And then you have the other side of feeling like we can’t move under our own power: the blocks that come with not yet having the craft to actually accomplish the big vision that you have and needing to develop that craft.

It’s a feeling all writers have felt, and it’s the feeling that Nicolas Cage’s character, Paul Matthews feels:

Maybe I’m being a passive main character in my own life. Maybe I’m not actually going for the things that I want. Maybe I’m just sitting there, while other people have the experiences.

Despite the fact that Paul Matthews, in Dream Scenario, is a passive person in relation to his greater dreams, he starts the film not as a passive main character but as an active one.

We meet a character who’s in this incredibly anxious place. He hasn’t actually done anything toward achieving that dream. But he has a very strong desire that he is pursuing.

You see, his old colleague from grad school has written a book about ants. That book about ants is based on a theory that, supposedly– at least from Paul’s perspective– Paul came up with back in grad school. And of course, it’s 30 years later. but he is really upset that his colleague is now publishing the book that he was meant to write even though he has not even started to write it.

Before the meeting, we watch him secretly set up his cell phone to record her so he can confront her and convince her to give him credit on her book.

All he wants in the world is credit– whether he’s actually done anything to earn that credit or not. And he’s pursuing that goal actively even though he’s by nature passive.

You can see how even his action of trying to get credit from his colleague is a reflection of this larger societal problem that the writer is trying to explore: people wanting credit without doing the work, wanting to get super-famous just for having a great idea, just for being you. Wanting to catch that thing that just happens to some people in our crazy social media-influenced world where people who have not actually done very much suddenly become the most interesting thing on everybody’s mind.

So this is what the character wants. Of course, he is not the most effective man, and this goes completely, completely wrong. He fails to get her to admit anything. In fact, the opposite happens. She confronts him for not having done anything. And by the end of it, he’s begging and pleading and making a fool out of himself.

And so we meet a character, who, even though he’s a sad sack, even though he’s a very ineffective character, is actually an active main character. Even though he is not actually writing his book, from a structural perspective he is driving his own story forward.

But then a really interesting thing happens, which is exactly what happens in social media. Without having earned it, without having chosen it, without having made a new choice, without having done anything, suddenly, Paul ends up not just in his daughter’s dreams but in the dreams of everyone.

Suddenly, everyone in the world is dreaming of Paul Matthews, this incredibly boring man. Paul Matthews has gone viral, but not on the Internet. He’s gone viral in people’s minds.

From a Hollywood perspective, even for a smaller film, this is a fantastic premise. It has a great hook. You hear it and you instantly think, Oh, that sounds interesting. I want to watch that.

And, at least at the beginning, it has an active main character who is driving the action of the film.

So from a commercial perspective, the film makes sense for its ability to hook its audience. From an execution perspective, that hook is well executed, which we’ll talk about. And from an acting perspective, the film has a fantastic cast.

But Dream Scenario also has a challenge: as the plot unfolds, instead of the movie happening by Paul Matthews as it is at the beginning, the movie starts to happen to Paul Matthews.

Now part of this is baked into the premise. Part of this is the fundamental challenge of the piece. Paul can’t have earned his way into people’s brains and dreams, because the sociopolitical issue that the writer wants to look at is the instant fame that people are achieving in our society and the effects of that– how it fuels a really complicated engine that is messing up our entire world: The advertising engine.

Sometimes you have to recognize that you have a premise that gets in the way of the primary concepts of structure.

Structurally, in an ideal world, we want a character making choices, driving their own story, driving the effects in the world.

We want them going on a journey that changes who they are or in which they fail to change.

And we want to feel like the movie happens by the main character rather than to the main character.

But the premise of Dream Scenario takes a guy who was really active at the beginning, trying to get credit, and suddenly propels him on to a conveyor belt that’s going to carry him through the rest of the film.

And this is what’s really interesting. Your film professor, unless they’re really experienced, is not going to notice that. Because your professor is going to be fascinated by what the film is saying, by its sociopolitical ramifications, by your beautiful dialogue.

And unless they’re really trained in structure, rather than film theory, they’re going to miss that.

They’re going to miss that when the character is on a conveyor belt, the audience is going to stop caring.

Because as fascinating as your intellectual ideas may be, the audience isn’t coming for your ideas.

(Sure, there is a very small percentage of your audience who are film professors, and are coming for the ideas. But there are not enough film professors in the world to make your movie successful).

The bulk of your audience is coming for an emotional experience.

And that means we need to latch on to a character and care about them.

And it is really hard to care about a character on a conveyor belt.

We want to care about a character who’s trying to get off that conveyor belt, who’s trying to make his own choices.

Kristoffer Borgli, the writer/director of Dream Scenario is aware that he has a passive main character problem, and makes several attempts to solve that problem in the structure of the screenplay.

But those attempts are not completely successful, for reasons that will be valuable for you to understand as a screenwriter.

Here’s what happens:

Nicholas Cage– Paul Matthews– goes from being a literal nobody to becoming “the most interesting person in the world,” as Michael Cera says to him.

(Michael Cera plays Trent, an ad executive from a company called, of course, Thoughts. It’s very unclear exactly what they do but essentially, they’re in advertising).

And all Trent wants is to work with Paul Matthews. That is all he wants in the world.

But of course, he’s not interested in Paul’s book about ants that Paul hasn’t even written. He’s not interested in biology. He’s not interested in helping Paul “pivot.”

He’s interested in Paul as an influencer.

From Trent’s perspective, Paul is the best kind of influencer: you don’t even have to open Facebook. He’s literally in your head.

And so what does Trent want? He wants Paul to sell Sprite. He wants Paul to try to get into people’s dreams with Sprite, to try to get the idea of Sprite into people’s dreams.

This, of course, is exactly what our entire influencer culture is built to do: to take somebody you like– whether you like them for good reasons or bad reasons or no reasons or they’re just famous– to take somebody who makes you say yes– and connect them to a product, so that product starts to feel like it’s part of your identity.

That’s how our commercial society is built.

Again, from a critical perspective, this Dream Scenario is making a fascinating choice. And from a structural perspective, they’re desperately trying to make Paul a more active main character.

They’re trying to get Paul to have a want. To bring him back to the superobjective of his book without changing his passivity as a character.

Paul ends up saying, (paraphrased), “No, I don’t want to sell Sprite. I want help getting my book out there.”

So it seems that at this moment, Paul is pivoting from being a passive main character to becoming an active main character.

And in most characters this approach would be successful.

But in this character, it’s not. And let me tell you why.

This main character still is not going to write his book. He’s not going to struggle with writing his book. He’s not going to think about writing his book and failing.

So what actually is happening in this scene is that the character is not pursuing a want. He’s pursuing a want-not.

This is one of the places where I see screenwriters make the same mistake again and again as they try to make passive main characters more active: confusing a want-not with a want.

Intellectually we understand that a want-not is a kind of want that exists in the world, but emotionally, it’s very hard to connect with a character who is pursuing a want-not.

We connect with characters who are actively pursuing choices.

So what ends up happening is that rather than feeling like Nicolas Cage’s character, Paul Matthews, is driving the scene, we feel like the scene has been hijacked by Michael Cera’s character, Trent.

It’s the ad guy who is driving the scene, rather than the main character, because he’s the one who has the strong want, which is to work with this annoying guy who just wants to talk about his book.

Everything Paul does is just a reaction to Trent’s want.

When a secondary character hijacks the scene from your main character, the audience starts to disconnect from the main character. This happens not on a conscious level– we’re not analyzing it– but on a subconscious, emotional level.

We find ourselves caring less, without exactly knowing why.

But the reason we feel this way is because the main character is on a conveyor belt, rather than driving the action forward. Because he’s primarily reacting to the wants of other characters rather than pursuing his own.

What’s interesting is that despite his overall passivity, Nicolas Cage’s character in Dream Scenario does have a want that could transform him into an active main character: He wants to be active in people’s dreams.

In fact, there are moments when Kristoffer Borgli activates this want quite effectively. But he still struggles to connect it to the overall structure.

For example, there’s this wonderful scene where Paul has just met with the ad executive. He’s just started to infiltrate the dreams of many people. And he’s just started to realize, I think a lot of people are dreaming about me. And out in the world, other people are also starting to make that connection.

We’ve met Paul Matthews at his teaching job, and we’ve seen how completely uninterested the students are in anything he has to say.

And then, one day, he shows up to class and he’s been transformed into an influencer. Suddenly there are kids in that class, who are not even enrolled in that class or interested in biology. Suddenly, everybody wants Paul Matthews.

And this is wonderful for Paul. In fact, Paul, who just wanted to get the students interested in biology, suddenly just wants all the kids to share their dreams about him.

This is an example of Paul being an active main character despite his passivity. Share your dreams about me is a change in Paul, and a want that he is actively pursuing.

But it’s still challenging to feel the structure, because just like Paul, all the students also want to share their dreams about him.

If you’re trying to turn a passive main character active in your screenplay, it’s vital to understand that in order for the audience to feel the want, it must push up against an obstacle.

In this scene, despite Paul’s clear want driving the scene, it’s hard to get the audience to root for Paul or feel connected to him because that pressure of want and obstacle is missing. What he wants from the students is the same thing they have come to give him.

Luckily, another obstacle comes up.

In all of their dreams, Paul is not doing anything, which, of course, is fascinating from a critical perspective, because it’s a reflection of who Paul is. It’s his central problem. He wants to be rewarded. He wants credit. He wants to be treated as if he’s achieved his potential without actually doing it. Without actually learning, without actually doing the work.

He wants just the idea to be enough.

And of course, it’s not. But then suddenly, Paul gets lucky and it is…

Suddenly, the idea is enough. Suddenly, they don’t even need the idea. Everyone loves him for just standing around in their dream. They feel great about him for just standing around innocuously in their dreams and not doing anything.

Suddenly, everybody in the world is in love with Paul.

Here we have a want. Paul wants to show up differently: to be active in people’s dreams. So as the story unfolds, the dreams are going to change, and that want is also going to come to fruition… though not in the way Paul expects.

But even though that want comes to fruition, and even though it causes a bunch of wonderful new problems for Paul, we still don’t get to feel the structure. We still don’t get to fully care, because none of this happens by Paul’s choices. It all just happens to Paul.

If you want to convert a passive main character to an active main character in your screenplay, it’s not enough just to have a want (rather than a want-not), or even an obstacle. We also need to have a choice.

For a character to feel active, the character must make choices to pursue their want. Those choices don’t have to work. They don’t have to make sense. But the character has to try.

Because if the character is not trying, we can’t feel their want.

Now, somebody could argue, Hey, Jake, the whole conception of the piece is that the main character doesn’t pursue any of his wants.

But that’s not actually correct. At the beginning, as we’ve already discussed, the character is actively pursuing a want, even though he’s ridiculously ineffective at doing it. And this makes us connect to and feel something about him.

There’s nothing wrong with setting a goal to write a script that breaks the rules, or where your character doesn’t make choices. But know that if you make that choice, you are climbing the hardest possible hill.

That means the rest of your craft needs to be so impeccable that it transcends that obstacle, otherwise you may impress the critics, but you’re probably going to lose your audience.

And you also have to ask yourself– is tying myself in knots over this intellectual conception of the film actually serving my premise? Or could I have explored it just as effectively if Paul had made some kind of choice that caused that change in the magic… and of his fate… that would ultimately undo him?

Might that have said something even more interesting about the nature of unearned fame?

Ultimately, these kinds of choices are artistic choices not structural ones. That means no one can tell you the right thing to do. But all too often, writers tie themselves in knots that they don’t have the craft to untangle, because they’re caught on a rigid conception of their characters that cuts them off from their full creativity.

If you’re going to make your character passive in service of a premise, you have to make sure that the end result is going to be worth it. You need a way around the challenges you’re creating for yourself so you don’t lose your audience.

Dream Scenario doesn’t quite find its way around the problems of its passive main character. The concept is brilliant, but the structure is hard to feel. Your mind is stimulated but your heart is not.

And that’s why on Rotten Tomatoes, only 68% of the audience likes this movie, while 91% of critics did. Because the critics are coming for the intellectual stimulation and the audience wants their hearts moved.

If you happen to move their intellect as well, that’s great, they will love you for that.

If you do both, as a film like Everything, Everywhere All at Once does, you will be greatly rewarded. But if you do intellect without emotion, it is really hard to make your audience care.

Here’s how things unfold in Dream Scenario:

Instead of Paul Matthews starting to drive his own desire to get active in people’s dreams, once again his wish is given to him without any choice of his own.

It begins when, for no reason, for no effort, for no choice made by Paul, Molly, the super hot ad firm assistant played by Dylan Gelula, admits that her dream about him was different.

In her dream they had sex, and it was hot.

The character has been given his want without even making stupid choices to try to get it. Nothing from him has moved the story forward. Rather, he’s been put back on a conveyor belt where the dreams of the external world are starting to change around him, and he’s reacting to that.

Sure, there’s an obstacle. Paul is put in a moral conundrum: he’s married. And she’s hot. And she’s flirting with him. But the character is so on the fence about whether he wants to be with her or not, that he’s not really pursuing her. He’s just kind of letting her direct him.

And the result is the exact same thing that happens in the scene with Trent, the ad guy. The scene gets hijacked. Paul is no longer driving the scene. Instead, Molly, the hot sexy assistant, is driving the scene.

Here, he’s neither acting on his want nor his want-not. He’s not making strong choices to avoid cheating on his wife. But he’s not also not making strong choices to cheat on his wife.

Rather, the scene is getting driven by Molly, the sexy assistant. And he’s letting it happen.

And like everything else he does in the world, messing it up. He can’t even just approach her the way that she wants. He ends up having a premature ejaculation. Nothing works. He’s a total disappointment to her. And of course he’s ashamed. And we’re ashamed for him.

Even though the scene is cringe-worthily fun to watch, it doesn’t do a darn thing for the structure. It doesn’t activate the main character.

No choices are made. No real structure is built because the character once again is on a conveyor belt.

The world is changing, his role is changing– it’s become a sexy role. That seems great, it’s more of what he wants– but he’s not making any choices to make that happen, and he’s not making any choices in relation to that.

He’s being driven by the secondary character, and the scene is once again getting hijacked.

Again, I want to amplify: it’s not that it’s wrong to write this way. This happens in real life sometimes, and things that happen in real life can happen in a movie. This film feels real as you watch it. It’s not that this kind of thing doesn’t happen or shouldn’t be the subject of films.

The issue is that it’s hard to root for passive main characters, so if you are determined to write one, you’re going to have to first make sure you’re doing it for a darn good reason, and then figure out some very creative ways to make us care.

It’s hard to root for passive main characters in movies, and it’s hard to root for passive main characters in life. And if you’re being a passive main character, it’s hard to root for yourself.

I really want you to think about that.

Are you being Paul Matthews? Are you hoping the conveyor belt of life will reward your talent and your potential? Are you waiting for the situation to change where you can finally have your dream?

Or are you being an active main character in your life? Are you making hard choices? Are you making new choices? Are you growing?

Are you pursuing your dreams or are you hoping your dreams come to you?

When you start pursuing your dreams, you’ll notice it becomes a lot easier to root for yourself, that suddenly you are a more attractive main character to you.

Because you’re making choices, you can feel your forward momentum, you can root for yourself because you’re actively pursuing your dreams, rather than just dreaming them.

You’re no longer telling yourself: It’d be nice if it happens… if the situation gets better… when I have enough money… when I have enough time.

No. You’re doing it. And it’s the doing that creates meaning, that gives you a feeling of structure in your own life.

You start to root for yourself. You become an active main character.

And soon, you’ll notice that other people start to root for you. Suddenly there are fans who love you, there are people who want to help you get where you’re going.

Because everyone connects to an active main character.

I want to amplify, it’s not wrong in your life to be a passive main character sometimes, and it’s not wrong in a movie to write a passive main character sometimes. It’s just really hard.

It’s so hard to root for them. It’s so hard to care about them. It’s so hard to be emotionally affected by them. And it’s so hard to be them.

We all want to be that person who’s pursuing their dreams. Those are the people that we fall in love with.

We fall in love with them not just because they happen to be famous, but because we admire them.

And what’s wonderful is, just like in a movie, the harder it gets, the more we root for them.

The more mistakes they make, the more we root for them.

The more bad choices they make the more we root for them.

Just like your characters, you’re going to make bad choices as you pursue a dream. You’re also going to make mistakes. Because some things you can only learn by doing.

But it’s not achieving the goal that allows us to connect with a character. It’s the journey of change brought about by the pursuit of that goal that allows us to connect.

To bring this back to Dream Scenario: by now you understand that Paul is not getting to really go on that kind of journey of change because he’s on a conveyor belt.

By now the plot of that conveyor belt’s getting “interesting,” but he’s still on a conveyor belt, and the scenes are still being hijacked by the characters around him.

And then the same thing happens again: the magic changes through no choice of Paul’s.

Instead of having sexy dreams about Paul, instead of having dreams where Paul’s just kind of hanging around and they feel good about him, people start to have nightmares about Paul.

People start to have vivid dreams of being horrifically murdered by Paul.

Now the writer is taking on the issue of cancel culture. The idea that one day you were “the most interesting person in the world” and now suddenly everybody hates you, maybe for good reasons, and maybe for bad ones.

(And I don’t want to get political, there are some people who deserve to be canceled, but Paul Matthews in this movie does not. Paul Matthews actually didn’t do anything. Only the perception of him changes).

All this just happened. And suddenly he’s being blamed. And conceptually, again, this is brilliant as a way of looking at a social problem. But it’s really challenging as a dramatic story.

It’s challenging because once again, Paul Matthews didn’t make a choice to change it, he didn’t invoke the magic, he didn’t do anything that created the change.

In fact, the change just happened. And he gets hunted by himself, in a really wonderful little dream sequence, which like everything else in this movie is brilliantly done. But even that doesn’t happen by him, it happens to him.

The result is that even though so many fascinating things are happening, and the writer is filled with so many fascinating ideas, and the execution is superb, it’s still hard to care– until finally the character does something.

Paul decides to finally do the thing he said he was never going to do– apologize.

And we finally get a scene we can care about. We get to see his apology, which starts off so authentically. He’s now experienced what his “audience” is experiencing. He has been hunted by himself, he now understands why people hate him. But of course, because he’s him, his apology quickly devolves into self-serving self-pity. And it’s wonderful to watch.

It’s a real choice, and he gets punished for it, and that punishment… finally… has happened by him…

So this is the thought I want to leave you with.

It is wonderful to attempt a film that breaks all the rules. And I think with a couple of tweaks, even a complicated, challenging film with a character who’s by nature passive, like Nick Cage’s character in Dream Scenario, can still pluck our heartstrings.

But to have a character who’s not primarily active is one of the most challenging forms of writing that you can do. And it means your craft needs to be perfect.

It means you need to look at the piece and look for every single opportunity for the character to get active. Even if their dominant trait is passivity. Even if their dominant trait is not making choices.

You have to think: OK, what are the obstacles? How do I push them to make a choice that they don’t want to make? How do I create the feeling that they are in some way involved or invoking or causing the things happening to them?

Because we don’t want to feel like the movie happens to our main character, we want to make sure it happens by them. We don’t want to feel like our character is saying no, we want to feel like our character is saying yes.

And of course, this is the same thing I want you to think about in your life. Are you pursuing a want or a want-not?

Are you pursuing your dreams actively? Or are you hoping that everything magically changes and they just come to you?

Are you rooting for yourself? Or are you making it so hard to root for yourself?

If you know structure, you know that whatever the character doesn’t want needs to manifest in some way in the movie. And the same thing is true in life.

If you are moving away from what you don’t want, rather than towards what you do, you are literally invoking what you don’t want at every moment.

This kind of thinking is exactly what gets in our way conceptually when we get afraid that the movie is going to turn into something we don’t want it to be, rather than curious about how setting ourselves free to new ideas can serve what we do want it to be.

“But he’s passive by nature! I don’t want him to make choices…”

Getting stuck on that concept is actually invoking the problem– allowing yourself to get ruled by it in your writing– rather than getting creative and opening yourself to the questions that would allow you to write the movie you do want, while also bringing your audience along for the ride:

For example:

How can an active character still reflect the problem of fame of our society, of being rewarded without doing anything to deserve it, while still actively pursing a goal?

You’ll suddenly realize there are a million things that Paul Matthews could do, in relation to his newfound fame.

You’d realize that, no matter how passive a person is by nature, new wants would certainly come up for anyone who suddenly becomes the most famous person in the world.

There are a million things that Paul could start to pursue– without pursuing his real dream of writing his book. There are a million ways to get his want activated, without undoing your premise.

And the same thing is true in life. Once you let go of the thing you don’t want, a ton of new possibilities that you couldn’t see before suddenly arise.

Try this: Pretend I just waved a magic wand. And suddenly, the thing that you don’t want becomes impossible. Absolutely impossible. So impossible that it couldn’t affect your life anymore. It couldn’t happen, even if you tried. It’s no longer a possibility in your life.

Ask yourself, what would I want then?

And you’ll start to notice that suddenly it becomes easier to be an active main character.

It is so much easier to live a life– or write the life– of a character that is not controlled by what is not wanted, but rather is making choices towards the thing that is wanted.

You will notice, both for your characters and yourself, no matter how big the obstacles– in fact, the bigger the obstacles, the better– that as you start to take those steps towards what you want against huge, seemingly insurmountable obstacles, that you start to root for yourself, that you start to root for your characters, that other people start to root for you, that suddenly a new level of empathy and growth occurs.

We think as writers that it’s the end that we’re building to, but it’s actually the process that gives us a feeling of structure, both in our movies and in our lives.

I hope that you enjoyed this podcast. If you are getting a lot out of it and it’s helping your writing, come and study with us. We have a free online class every Thursday night, foundation classes in screenwriting and TV writing, a Master Class for those of you who want a grad school education at the tiniest fraction of the cost, and a a wonderful ProTrack mentorship program that will pair you one on one with a professional writer, who will read every page you write and mentor you through your entire career at less than you would pay for a single semester of grad school.